SIARHEI YAZLAVETSKI

Love, Longing, and Life in Transition

Siarhei Yazlavetski, originally from Belarus and now based in London, UK, is a versatile photographer with a passion for landscapes and documentary photography. His work delves into the realms of self-reflection and the creation of surreal worlds, inviting viewers to explore new facets of themselves and their surroundings.

Drawing from his diverse educational background, including master’s degrees in Computer Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Applied Neuroscience, Yazlavetski explores the interconnectedness of ideas, concepts, and the human experience.

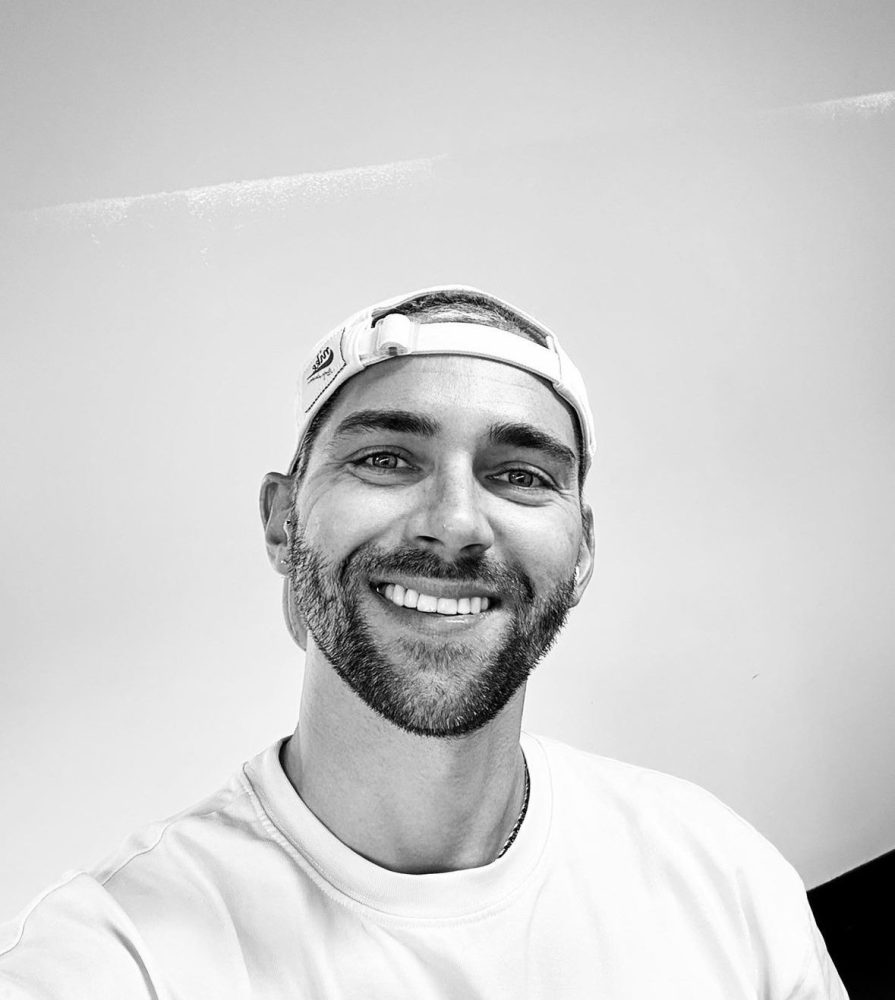

»Journey to Eden« (2023–2024) by photographer Siarhei Yazlavetski and art director Aleh Razhkou, is a poignant documentary photography series that delves into the profound self-reflection of a gay couple from Eastern Europe. This couple found refuge in London against the tumultuous backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Through the ingenious use of long exposure and other techniques, the photographs aim to vividly illustrate the couple’s profound anxiety and emotional turmoil. The deliberate distortion of their bodies during the extended exposure mirrors the chaos of their past and present uncertainty, creating a powerful visual metaphor. Amidst this turmoil, some images gently capture their intimate moments, accentuating the idea that their unwavering love and support provide solace and strength, much like the vibrant plants that adorn their Eden-like home.

This project delves into the themes of resilience, sanctuary, and monogamy. It raises thought-provoking questions about the impact of migration on a relationship—has their love evolved or transformed since moving to the UK? The alluring world of open relationships and a multitude of potential partners presents new opportunities, but also potential challenges.

ALEH

I grew up in Belarus, surrounded by Soviet constructs with scarce fragments of Belarusian identity. We inherited a patriarchal culture and a cult of impersonality from the USSR.

I was about eight when I first learned about gay people. My mother was watching TV when suddenly she exclaimed with a grimace of disgust, »Ew, queerness!« On the screen were two men kissing, caricaturally mannered and effeminate. This is how I learned my first lesson from my parents: being gay is disgusting. I felt ashamed, deep down, suspecting that I might be gay too. Moreover, growing up, I understood that my queer identity could be obvious to anyone.

Everything, from the tone of my voice to my gestures hinted at my true nature. Therefore, I realized that in order to be accepted, I needed to become »normal«. Mimicry of heteronormative behaviour became my survival strategy. Everyone could tell I was different, but as long as I continued to act »normal,« they tolerated me. I recognised that my authentic self was considered flawed and worthless according to the local culture. The process when the society cuts off one’s ability to express who they are can be described, in my opinion, as a »social castration«. It is a silent process which involves colleagues, friends, and relatives.

ANDREY

I’ve been thinking about migration since I was a child. My mother told me stories about moving from Uzbekistan to Ukraine, about what it felt like to be a stranger among your own kind, about acceptance and adaptation.

As a child, I tried to understand what it was like to lose the language I spoke, jokes, friends, context. To lose the home where you can walk at night with your eyes closed without a stumble. Familiar roads, streets, parks, all of this was in my head when I closed my eyes and thought of home. I clearly understood that I did not want to lose these images.

Having moved to London, the images of home were replaced with white noise. Opening my eyes, as if through rose-colored glasses, I saw a beautiful picture. In it, people showed interest in how I was getting on, but I didn’t feel they really could relate to my struggles. Later I would learn that it was for out of politeness.

ANDREY

I was in Disneyland that my partner Aleh and I came to for a while. With a breeze in our faces, we rode up and down the roller coaster in a bright passenger car. One moment, you experience joy, pleasure, and excitement, and the next–fear of the future. Sometimes even horror, which makes you want to scream hysterically. At such moments, I wanted to close my eyes and stop everything, but the train wouldn’t stop. We clearly understood that there was no way back. We were strapped in the roller coaster car and the only way was onward.

ALEH

When there is no space for one, let alone for a couple; intimacy between queer people could only exist within trustful bubbles among supportive people. Elsewhere, it turned into activism, an act of protest. I kissed on the streets of Minsk and Kyiv, always first looking around and assessing the level of danger.

ALEH

When I moved to the UK, I noticed that people had boundaries within which their identities safely exist. Surprisingly, I found this space around myself too–everyone respects my boundaries. Along the way, I started gaining my sexuality and creativity back. I realised that a massive part of my energy was consumed by restraints.

ANDREY

My personal roller coaster passed through exploring the city, learning the foreign language, making friends, therapy sessions, deep emotional engagement, passionate sex, sincere love.

ANDREY

This journey strengthened my relationship with Aleh. Going through it together, we took care of each other, expressed our feelings, explored open relationships. Now our connection is one of the pillars of my foundation, which helps me stand while moving at such pace. I also found acceptance and support from my parents. Although we are far from each other, I feel them close by.

»Balance found«, my yoga teacher says. And I feel it too–I’ve found balance and standing firmly now.

ALEH

My relationship with Andrey also transformed here. For the first time, I felt that we existed as a couple. We neither needed to hide our loving glances behind a veneer of indifference in public, nor lie about being brothers when renting an apartment. No more maintaining this facade for neighbours and work colleagues. We no longer needed to waste energy on endless lies and disguises. Instead, that energy could be invested in our future.

ANDREY

I’ve learned to look straight ahead, walking down the street, not tilting my head back to look at the buildings. I will definitely find my way home if my phone dies. A smooth rise up and levelling out. Our apartment became cozier, plants took on new forms, vintage pots replaced white ceramic, and local friends started to notice that my accent no longer jars.

I’ve definitely grown up, reconsidered my views and priorities. The roads of the old home remain only in my memory, but the connection with my family is strong. The roller-coaster ride has come to an end. I can unbuckle the belts. We are home. It’s already safe.

ALEH

After living here for two years, our relationship has grown stronger. It is filled with love, respect, trust, and freedom.