Atefe Asadi

Iranian poetess Atefe Asadi–on the freedom and power native language gives you, translation losses and memory that at times could be very cruel

Atefe Asadi is a writer, poetess, editor and translator from Tehran, Iran. In Iran, she worked as editor and translator with various publications and magazines, including the underground ones. Asadi’s literary work is set in the context of Iranian society and addresses the country’s social, political, and religious issues, gender, sexuality, and women’s rights and challenges conservatism, religion, war, and their consequences. She tries to present a realistic account of life in today’s Iran under the shadow of dictatorship from a variety of angles and perspectives and using different voices, narrators, and points of view. Her three story collections were rejected by Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and declared unprintable.

While in Iran, Asadi was under pressure due to her work with underground literature and civic activities. She was interrogated on numerous occasions and was arrested by the security forces. After the release, she was unable to continue her activity in Iran and was forced to close her social media accounts for months. In December 2022, Asadi took up the ICORN residency in Hannover, Germany, through the Hannah Arendt Scholarship. Since then, she has been following her literary and social activities in a safe atmosphere.

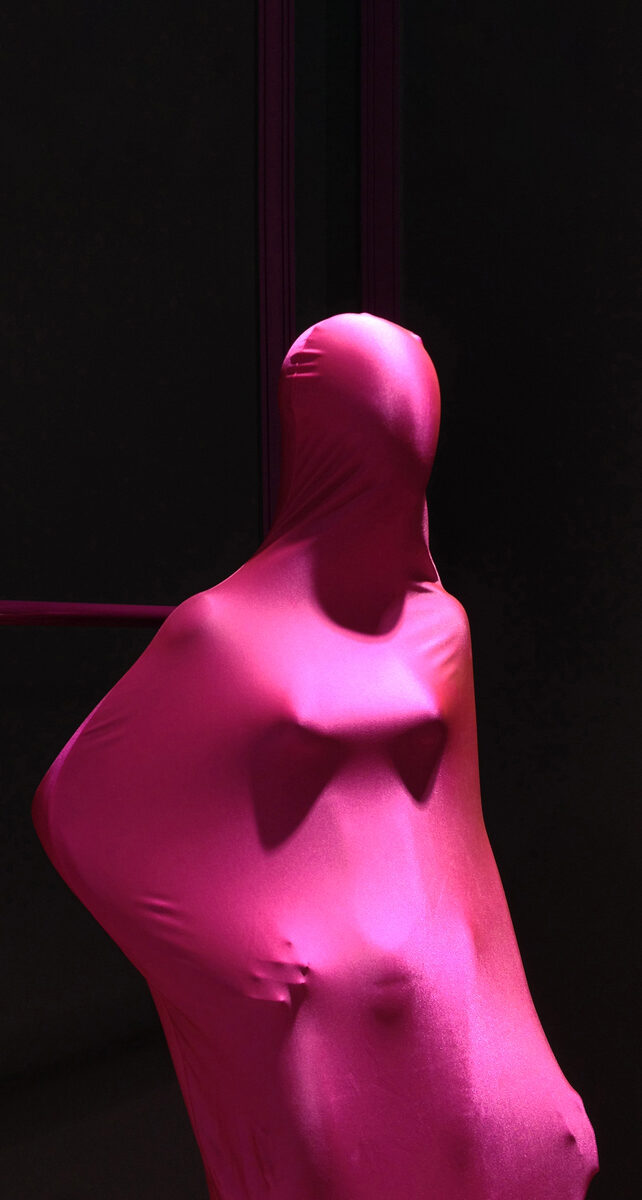

Juli Nazarova is a Belarusian photographer and retoucher. She is author of the several photo projects (Varvara’s Tales, the Time of Transition. Puppet Dress, etc), shown in group and solo exhibitions in Belarus, Spain, Russia, Canada, Latvia, Armenia and Germany. The main themes of her work are: reflection on childhood, exploration of her daughter’s world, and the search for female identity and inner strength. Photography for her is a way to create a unique world, erasing the boundaries between memories and reality, and finding hidden feelings. She is currently based in Georgia.

Despite the distance of 3,000 kilometers between them, Belarus and Iran share striking similarities in their political and human rights situations, both being authoritarian regimes run for decades by the same dictators who suppress dissent through censorship, imprisonment, violence, harassment, torture, and unfair trials. The states apply severe repression of any dissent manifestation, with over 1,700 recognized political prisoners in Belarus and thousands in Iran–in both death penalty is enforced (with Belarus being the only European country to do so).

Free media is non-existent in them: prior to Russia’s invading Ukraine, Belarus had been Europe’s most dangerous place for journalists, while Iran has been subjecting its press to strict censorship and frequent arrests, particularly following the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests.

Maria Kolesnikova–a leading opposition figure and a fighter for democracy in Belarus, now imprisoned and in severe health conditions; Nina Bahinskaya–a 75-years-old activist known for decades of fearless one-person-campaigns in the capital’s center in front of governmental buildings; Nasrin Sotoudeh–a relentless Iranian advocate for women’s rights surviving jail and cruel punishments; Masih Alinejad–a journalist and founder of online movement »My Stealthy Freedom«; Narges Mohammadi–a journalist and human rights activist awarded Nobel Peace Prize in 2023 and now held at Iran’s notorious Evin Prison, which houses political prisoners and those with Western ties. Are these countries really so far from each other?

These are just a few from the long list of female freedom and justice fighters who continue playing a crucial role in resisting these authoritarian regimes, leading protests and enduring imprisonment, making them symbols of defiance against state repression. Today–many of them in forced exile, far away from their families, friends and communities. One of such activists is Atefe Asadi–a young writer and poetess whose underground work back in Iran has caused her to flee Iran and arrive to Hannover, Germany. PlatformB presents a talk between Atefe and Olga Bubich, a Belarusian writer and journalist in exile.

Just like me, you arrived to Germany in December 2022–probably the worst season one can imagine for the exile to Europe. Do you remember your impressions of Hannover? Was there anything that made you feel warmer?

In the first days, all I thought was that »Ok, I am just a passenger here!« but the truth is I didn’t want to open my suitcase…. Every morning before opening my eyes, I imagined myself in Tehran, in my bedroom hearning my »myna« bird call »Atefe! Atefe!« to wake me up. But then I would look around and see that I was in a house where I didn’t belong. In Hannover, I am surrounded by lovely supportive people, but the sense of belonging is an internal thing, and nothing can fill that hole in the heart. I was looking for familiar smells and tastes–anything that could connect me to home, promise the return–I wanted to hear the voice reassuring me that all was temporary.

I missed the odor of our kitchen at noon, I missed my grandmother’s attractive spices, the smell of my bird’s wet feathers after bathing… and beyond those, there were things that are hard to explain. For example, I was walking in Hannover and looking for the smell of car exhaust, the smell of traffic of the city I knew and recognized. I was looking for a taste I could tell others I knew! I wanted Ghormeh Sabzi, a homemade food that cannot be found in any Iranian restaurant the way it is made in Iran. Or maybe it is the presence of these memories in Iran that gives meaning to the smell and taste, not the smell and taste itself. I sniffed everywhere and found nothing.

ATEFE: Human memory is very cruel. It is only when you have nostalgia, you realize how densely everything has been recorded and kept somewhere at the back of you mind–with details of taste and smell included.

Moreover, the German winter was a new phenomenon for me. One day, because I didn’t know what kind of shoes and socks were suitable for that season, my toe blistered and reddened so much that I was terrified. However, even if I had arrived to Europe in summer, I would still freeze from the cold homesickness flowing inside me–I was surrounded with unknown words, objects and sounds…

Belarusian exiled poetess Volha Hapeeva explores her feelings in foreign countries through languages she learns, speaks and writes, comparing them with clothes one wears for different occasions. But those new »outfits« cannot but also shape our our identity and behaviour by their origin, photetics and grammar structure.

»The English word foreign (used to describe language) comes from the Latin foris, literally out of the door, and is related to foris [a door]. In English, though, we say something sounds strange, not foreign or someone else’s property. The Belarussian variant for foreign is zamiežnaja mova, which means beyond the borders,« Volha writes. And in this regard, I would like to ask you about your liguistic wardrobe and relations between Persian, English and now also German–in your new everydayness, but also in your writing. How do you feel and where do you see your/their place? Which doors do they open or close? Which borders they mark?

I must say that during the first year learning German felt like a wall to me. And whenever I tried to confront it, it resulted in a head injury. And I am still wounded by it… At the same time, I do believe that learning a new language is similar to opening a new door–or a window that allows seeing a new world.

My Farsi is the raw material for writing. Farsi is the language that shapes and articulates my every thought and I have to protect it…. It is the language of my dreams and my nightmares. I cry in Farsi. I laugh in Farsi. I miss those crowded alleys filled with Farsi–something I don’t have here in Germany. As I am a very sensual person, with any other language, I cannot be my Persian self. But then English words come to my tongue… and the next morning I have a German language exam! With all three languages spinning in my brain, it’s far from being easy!

My teacher says one should learn to think in German in order to improve speaking skills. But every time I try thinking in another language, I feel guilty. Would if my Farsi gets upset with me?

And at which point did you write your first poem after leaving Iran? What emotion »called« you to write it?

In general, I can’t say that writing is a part of my life. But at the same time it has been my whole life! It’s as essential to my survival as eating, drinking, and breathing air.

The father’s character in the movie Big Fish once said, If I’m not in the water, I’ll dry up and it resonates with what I feel about writing as a creative process. I can’t really say I’ve been away from writing even in the worst moments of my life. Maybe I haven’t been able to focus on it as much as I’d like, invest time into it, or get a result that I’m 100% happy with (because I’m so self-critical), but I’m always forming an idea for a story or a line for a future poem in my head. I just can’t imagine thinking or living any other way!

For me who writes both stories and poetry, poetry is a different medium. Sometimes, when I feel I should be less talkative but more striking, the poem takes my ideas, pours them into its form, and calls me to complete writing.

Thinking back… I probably can’t name a specific moment when I started writing poetry–I just know that, whenever I was sad as a child, I used to write. For example, when my grandmother passed away when I was ten, I dedicated her a poem full of problems. I used to listen to music, tried to mimic the lyrics, and craft my own words based on their significance. I wanted to benefit from the power of creating the magic word because I saw people enjoying hearing it in different ceremonies.

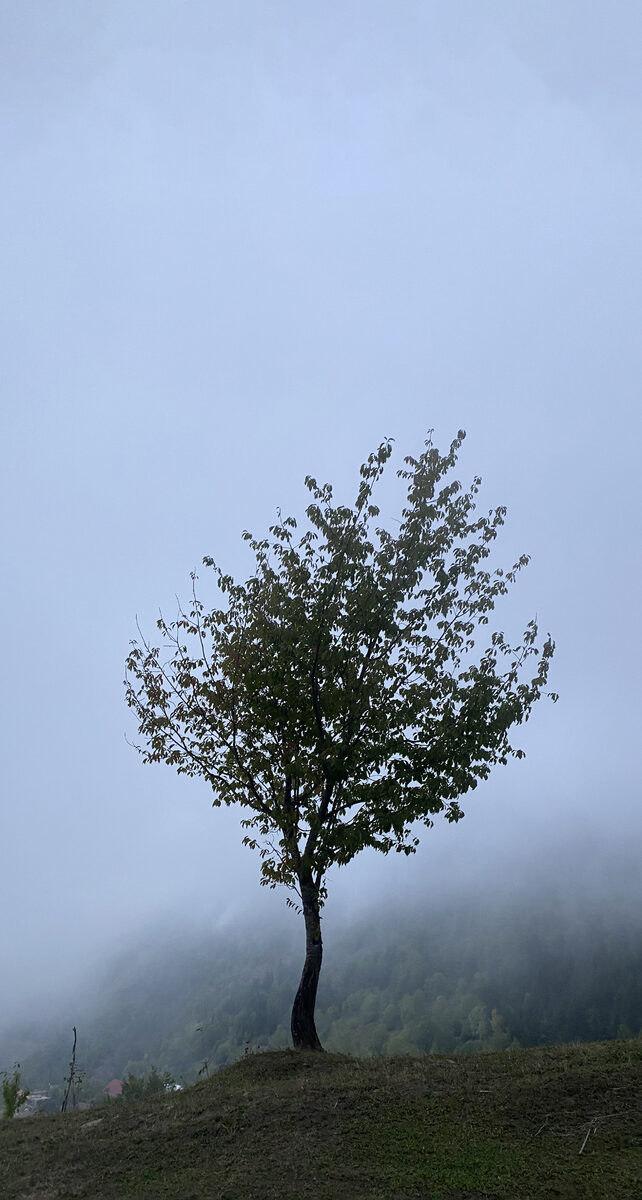

And my first poem in Germany…. The initial line emerged as I departed Iran and took its final shape in the days that followed, prompting me to jot it down on my mobile phone. At first, it came as an image of a young dead sapling, then my mind got filled with the faces of my family and the tears of farewell….

How do you feel about your poems translated into German or other European languages? What is most challenging about this process?

When it comes to translating, I always want to actively participate in it, contributing but also finding out what happens to my original work. How much of my poetry in Persian has survived in German? How much of my story character’s tone is left in German?

I am certainly happy to see works translated, but we know that translation is both a bridge and a wall. After translation, my poem will no longer be Persian and I have to accept it, sacrificing the words. In addition to my texts, I need to deliver myself and my feelings to a translator, too!

There are two key aspects in my poetry translation. The first facet pertains to rhythmic poems, characterized by a specific prosody and rhyme scheme (which makes me especially sad because those almost inevitably are going to be lost in translation.) In many ways the effectiveness of that rhythmic word depends on observing the rhymes, for example:

Khoon & Jonoon & Ostekhoon

خون

جُنون

اُستِخون

Blood, madness and bone

or

Tan, Pirhan, Zan

تَن

پیرهَن

زَن

body, short, woman.

Persian poetry is translated in two ways: either as in a free rewriting or when an attempt is made to preserve the rhythm and rhyme as much as possible. For example, Mr. Ali Abdullahi, a very good Iranian poet and translator, translated some of my poems into German following the second approach–something I believe to be very important. Although, truth be told, his version of a poem is a new poem itself…

The next challenge involves the preservation of certain images and cultural references. For instance, in one of my poems I explore the emotions of a narrator–a war fighter’s daughter–who finds her father very much transformed after his return from the battlefield.

The verse starts with the father entering the house with a wreath of flowers around his neck. The people who see him burn Esfand اَسفَند

and send welcoming Salavat صَلَوات blessings–both linguistic peculiarities untranslatable… .

Moreover, I would like to emphasize that this man suffers from mental issues as a result of his proximity to the explosions occurring during the war. In Farsi, the term Moj موج signifies both a sea wave and a person in shock and severe injuries due to war. The young girl then asks her father, But dad, how did this happen to you? Is there a sea in the land fronts of the war?! Although the translation retains the shock after the shelling, it loses the image of the wave and the sea, along with its connection to the soldier’s mental fluctuations and turmoil the way it senses in Farsi.

»Free in the Wind« is one of the recent songs written by Atefe Asadi.

Music and performance–Farzad Beni.

This song, set in the era of the Woman Life Freedom movement, honors the courageous and determined Iranian women who spearhead this movement, risking their lives with every step they take on Iran’s streets without the mandatory hijab. They continue to fight, and in doing so, each one creates the revolution. Because knowing that we are fighting without going back is an important part of victory.

ATEFE: Another example of meaning losses is a poem by Mehdi Mousavi that has a social-political references. One of its lines reads as follows: An endless 18th of July is in your Bahman cigar.

Bahman is both the name for the month of February when a heavy snow suddenly descends from the mountains and a famous old cigar brand. But this is not all. Bahman is also the month when Khomeini came to Iran and began the Islamic Revolution. The challenge lies in effectively conveying all these references in translation simultaneously, as Bahman alludes to both the revolution, the chill of destruction, and the cigar brand.

Next, we arrive at an endless 18th of July, which stands for the anniversary of the repression of university students in Tehran–a date deeply ingrained in the collective memory of Iranians. Also, July in Persian is Tir (تیر) which means an arrow or a bullet–another symbol of killing and repression. To keep all these meanings, we would need–for this one short line only!–at least six footnotes! As a result, this stanza would surely die in translation whatever expert the translator is. And our foreign readers would die because of boredom!

In your recent talk at LCB as a part of »Literaturen im Exil« series, moderated by Daniela Seel, you mentioned a big role poetry plays in Iran and its everydayness. Could you dwell a bit more on it?

How and why did it start being so important? And does it still have much influence on people?

Atefe: Poetry has always been closely connected to the Iranian culture and language–and in fact, to the daily lives of the Iranians in general. I would say it has been inseparable. During Nowruz Eid [Persian New Year] and at the Haftsin table, many people who believe in Islam put the poetry collection of Hafez’s [a Persian lyric poet who lived in the 14th century] next to the Quran. But poetry has a very high status even for non-believers or people who are not serious readers of literature.

One of the reasons of poetry’s being such an indispensable part of our life is the Persian language itself that has a high capacity to create rhythmic words and metaphors. Ferdowsi [a poet, one of the most influential figures of Persian literature (940–1019 or 1025)] endeavored to preserve and revitalize the Persian language by penning his epic poem »The Shahnameh« over a span of 30 years.

Poetry has a powerful position even today. It is bitter, but the number of poets locked in prison, exiled, or killed proves this.

Examining history from the past to the present reveals the governments’ approach to literature, from Farrokhi Yazdi, a 19th century journalist, politician and a poet with sewed lips, to Baktash Abtin, who the government killed due to treatment deprivation, or Mehdi Mousavi, who had to flee Iran because of poetry.

The control of public expression–also in the form of poetry–is extremely harsh. Many young poets, even not very famous ones, are incarcerated simply for publishing a poem on their social networks, or forced to pledge to never be active online again.

But people continue fighting: they shout poetry-based slogans during demonstrations and at sport events with the rhythmic words clearly contributing to collective unity formation. Witnessing the efficacy of eloquent speech, we see it transforming into a real combat weapon.

Political poems written during revolutionary crises might lack the necessary depth–because they are more about an emotional charge, right?–but they do contain anger and a message that encourages unity and intimidating the governments. Ordinary people may not have time or expertise to read lengthy political analysis articles, but a poem or a piece of music can inform them and make them feel a part of the revolution or a protest movement.

For example, Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian revolution, published a book of poetry under his own name (although nobody knows if he was really a poet or not), and Ali Khamenei, the current leader of Iran, whose hands are stained with people’s blood, is a poet, and every year he organises poetry readings and invites government and affiliated poets! Why does he do it? Because the dictator is aware of the power of literature and the popularity of melodious words among the people. He is the most powerful person in Iran, but he also likes to pretend to be a popular poet and direct the literary stream power towards himself and his own goals!