Liza MUR

Textile artist Liza MUR discusses her work supporting Russian political prisoners, how embroidery helps in processing tragedy and fighting for rights, and why the personal and political are inseparable

Liza MUR is a Multidisciplinary artist, teacher. She was born in Leningrad, Russia, 1991. Currently based in Barcelona, Spain.

Liza MUR works primarily with textiles to explore themes of resilience, displacement, and freedom of expression. Originally from Russia, she moved to Spain following the full-scale invasion and tightening of the dictatorship—an experience that profoundly shaped her work.

Through collaboration and teaching, she empowers others to express personal stories within broader social contexts. Her participatory and collective work embodies the belief that »the personal is political,« drawing on the legacy of feminist textile art—from suffragette banners and Chilean Arpilleras to artists like Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Judy Chicago and Tracey Emin.

A common thread in Liza’s artistic practice is a dialogue with the

environment—moving from a safe, vibrant home world to political, urban, and natural contexts.

For many outside of Russia, it is difficult to grasp the extent of military propaganda, repression, inhumane laws, long prison sentences, and conditions for political prisoners, while Russian artists living in safer countries explore various ways to communicate with audiences both inside and outside Russia to continue opposing war and dictatorship.

Why is textile art your primary medium for expression? Is it more about feminist practice, the meditative nature of the process, or the accessibility of the material?

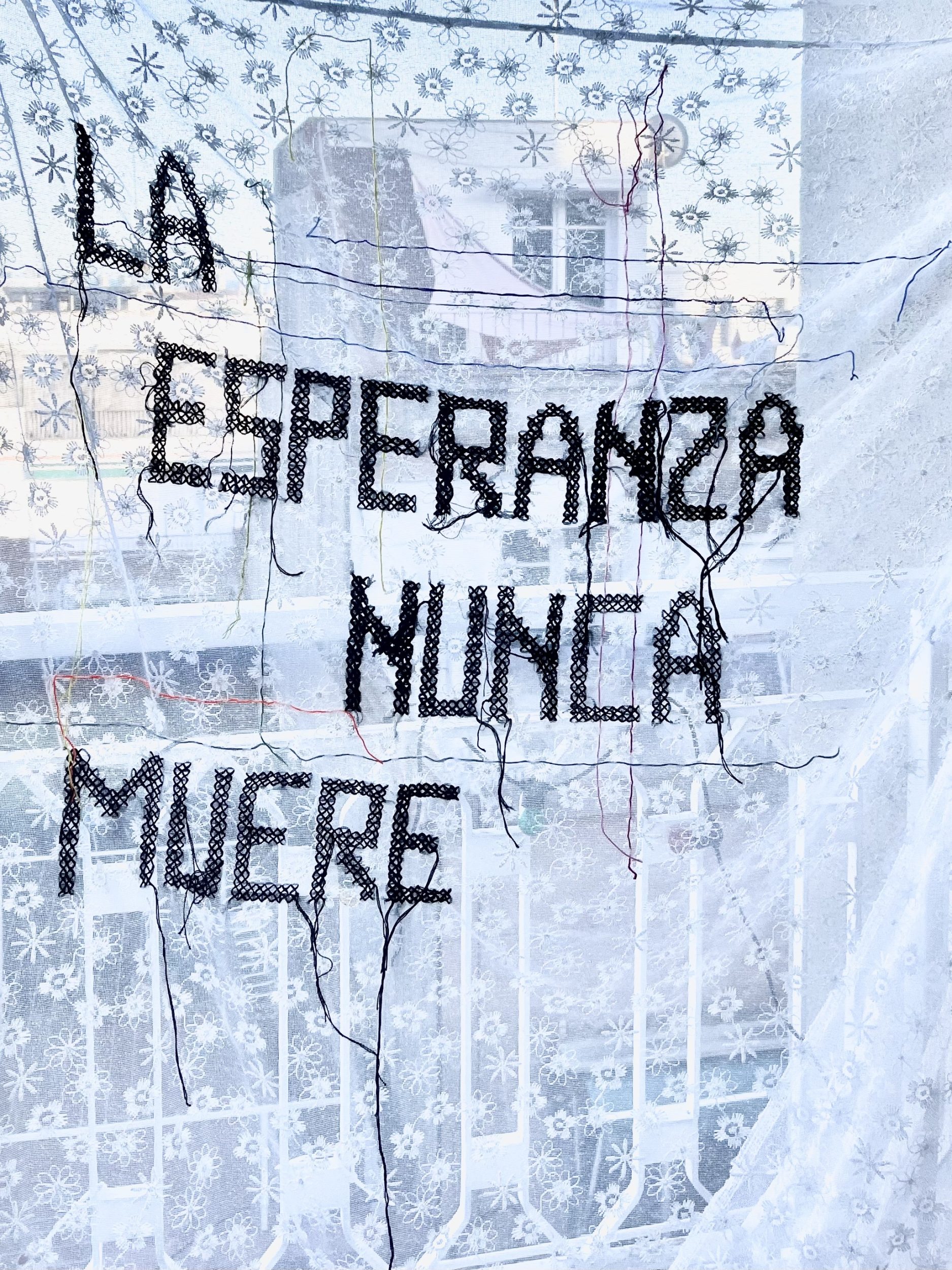

The textile medium carries the legacy of domestic labor, which was long undervalued and deemed unworthy of attention. Now, it has transitioned into a different realm—what was once a form of oppression has become a voice for dialogue. For me, embroidery is about feminism, tradition, and accessibility. I can easily pack everything up and move to a new place at any time.

I also love the tactile nature of the medium because it’s pleasant to work with. When you’re reflecting on difficult topics, the softness of the material feels almost supportive, like it’s helping you process and express those complexities.

Many of your works document significant political events, often tragic. How do you decide which events are important for you to address?

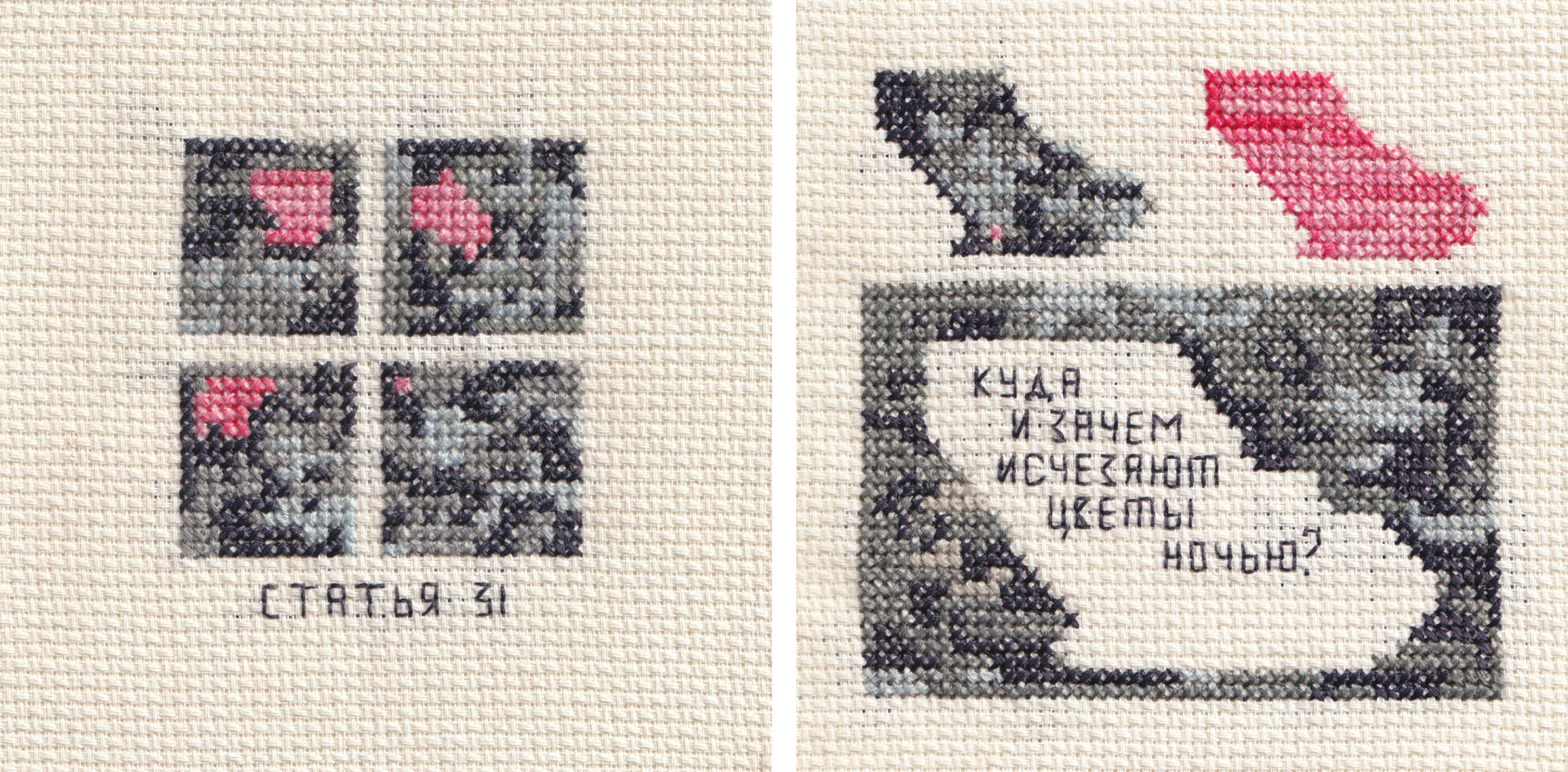

It’s something intuitive and emotional—what resonates with me the most. For example, I created a small triptych about the death of Navalny. What struck me most deeply was how, after the funeral, many of my friends in Moscow brought flowers every day to the Solovetsky Stone, a memorial to the victims of political repression.

One of them told me that the flowers would disappear overnight, but she kept bringing them back the next day. I was moved by the fact that, despite the danger, people continued doing this, even though it might seem like an action with no tangible impact. It was important for me to capture this moment [through my embroidery]—to co-exist with these people in spirit when I couldn’t be there physically.

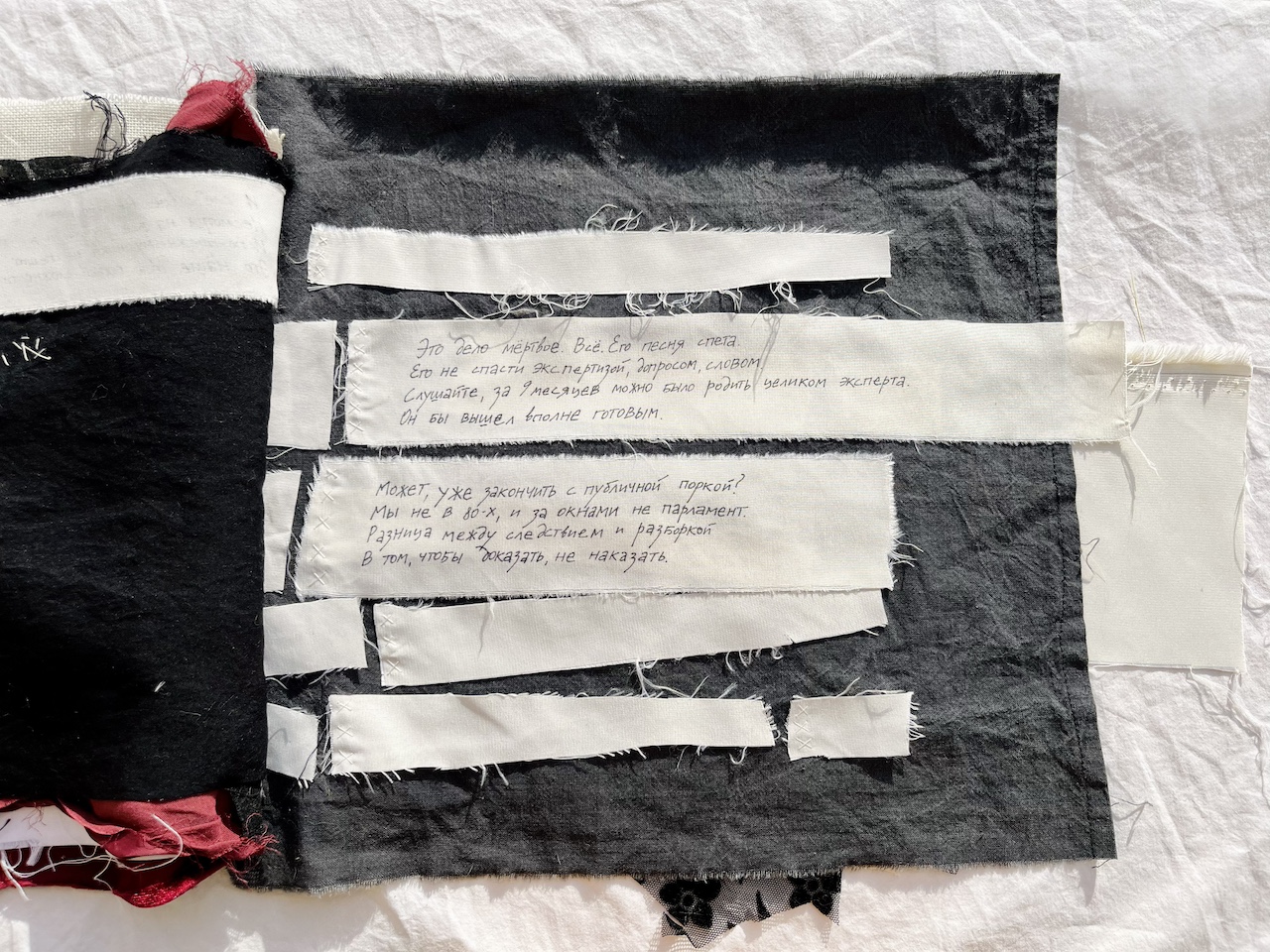

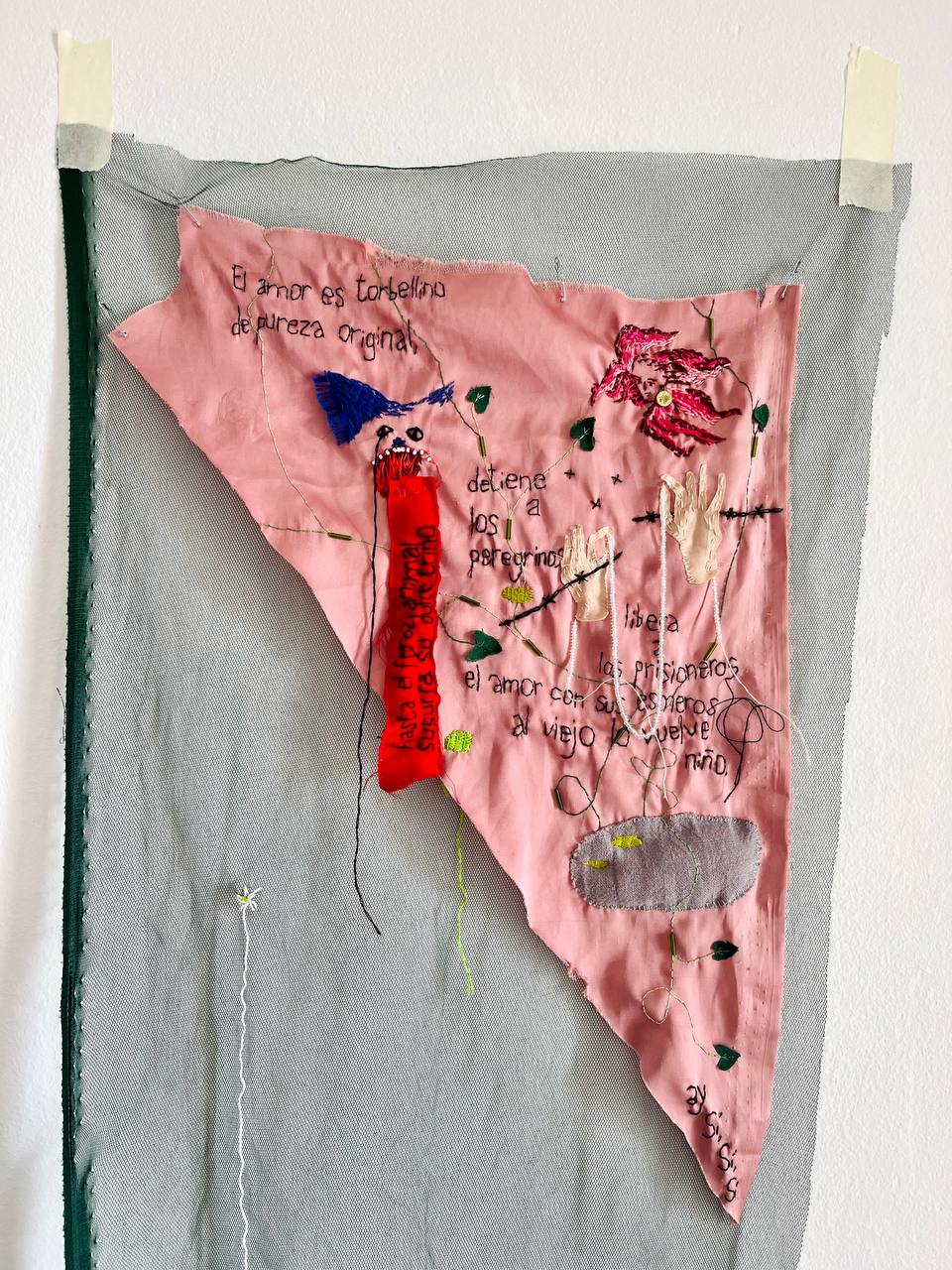

I also created a textile book about Zhenya Berkovich and Sveta Petrichuk. I watched their performance »Finist the Bright Falcon« online, after the criminal case was opened against them. The book was a response to both the performance and the speech in court. I wanted to draw people’s attention to this case.

Creating art about current tragic events is important to me physically as well, as it extends the moment of reflection. We endlessly scroll through news–there’s so much of it. Embroidery, for me, is an opportunity to pause on one of these events and, in a way, fully experience it.

The book about »Finist the Bright Falcon« appears as a performative object—it interacts with the viewers, and the story is told not only through the text. Could you share more about the structure of this object?

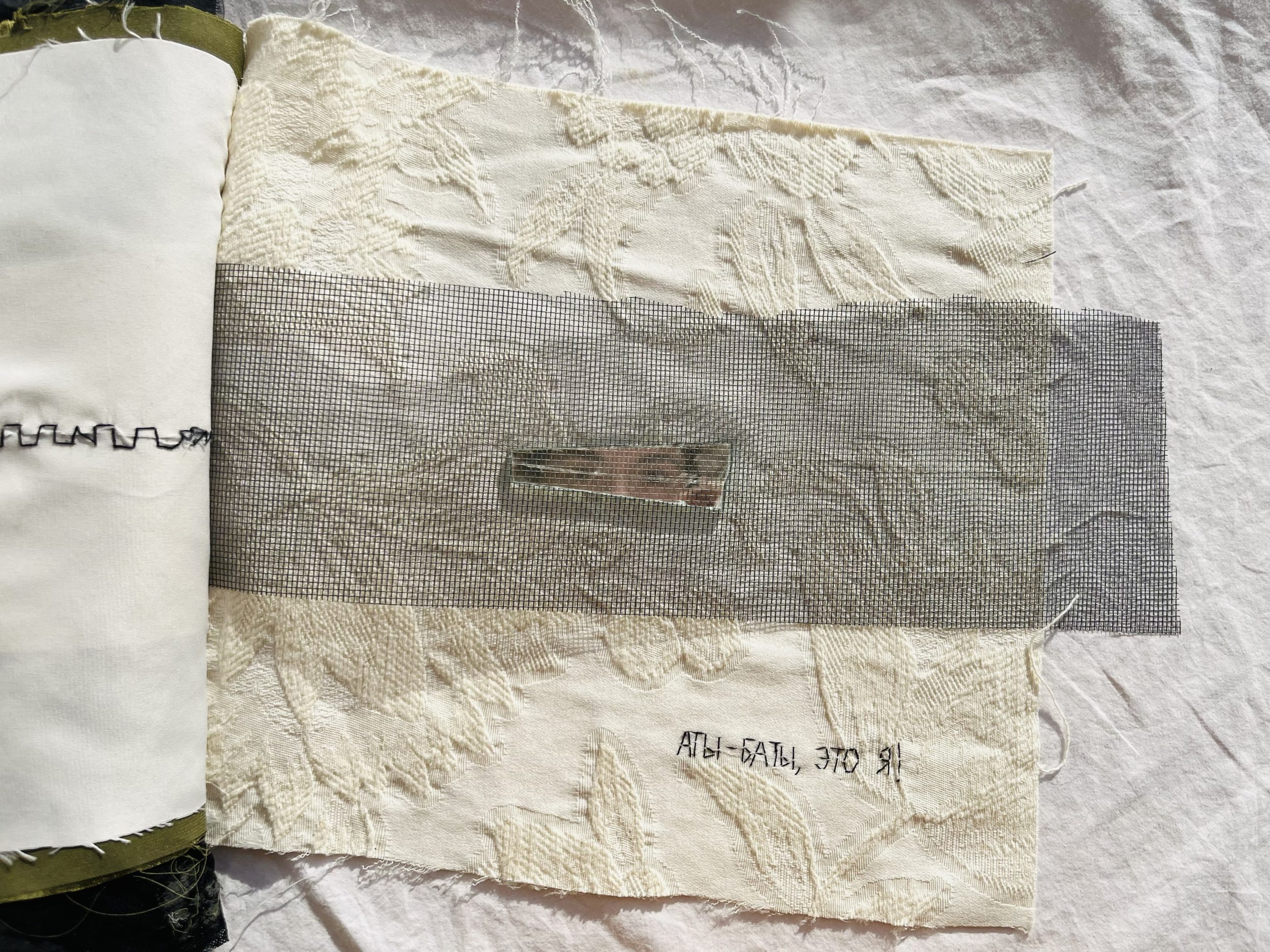

I was deeply moved by the recording of the performance—how the lighting, costumes, and text were all so thoughtfully crafted, along with the fairy tale itself. I remember watching the film »Finist the Bright Falcon« as a child. My book has two layers: one layer is the court speech on white fabric, and the other layer conveys fragments of the performance through different textures.

I tried to reflect the heroine’s journey—how she meets someone, then leaves, and is promised many things, but eventually faces disappointment. As you turn the pages, the layers gradually overlap, and at the end, there is a rhyme-question: »Aty-baty, who’s coming out? Aty-baty, it’s me!« So, the final page is a broken mirror—where the viewer looks at themselves.

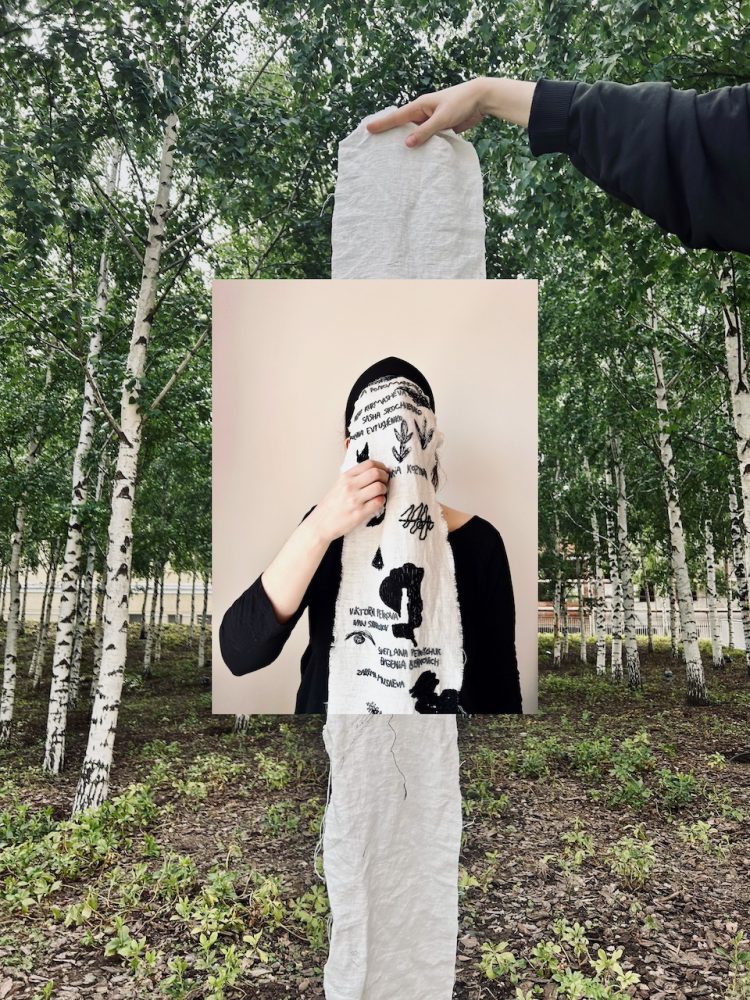

The book is wrapped in a headscarf, and on it is embroidered an open letter »O.« In the play, there is a line: »An important part of the uniform is the headscarf, which you must wear at all times outside the camera. This is necessary so that the prisoners don’t get the wrong idea that they are equal to the guards. Put the scarf on your head. The two ends should hang over your shoulders. Tie the scarf under your chin. Open your mouth, as if pronouncing the letter ‘O’, to make sure the scarf stays in place.«

This reference to the headscarf, with its symbolic power and intimate connection to control, is also mirrored in the structure and meaning of the book. It’s not just a narrative—it’s a way to actively engage the viewer, to make them confront their own reflections within the context of these events.

You create collective textile projects remotely. How do you gather materials for such pieces?

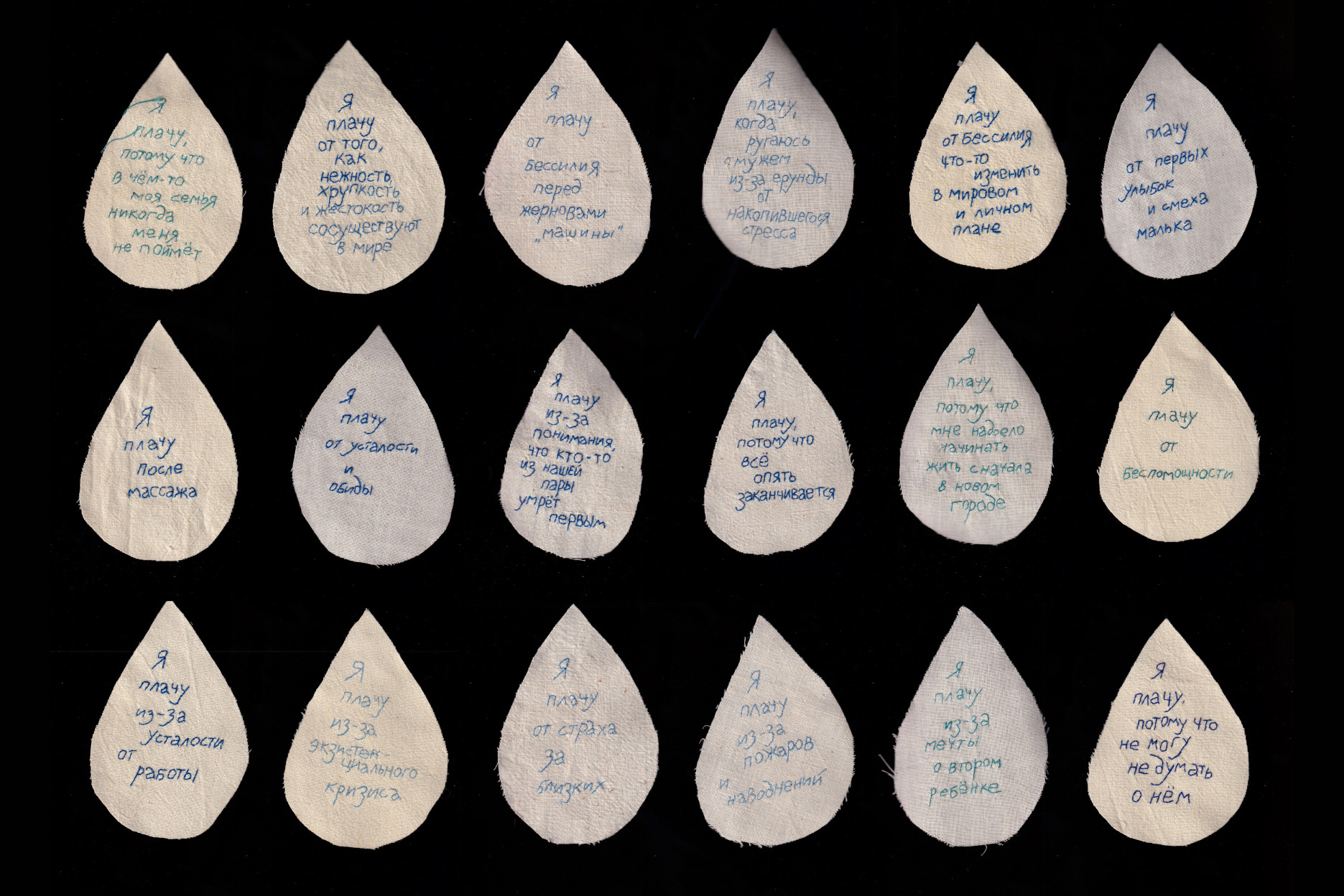

I feel immense support from the people who participate. For example, in the »I Cry« project, I asked people why they cry, and their stories deeply moved me. Everyone cries for different reasons, and my goal was to show that all reasons for crying are equally valid—whether it’s personal sorrow, war, or other tragic events. The project involved women, and only one man—my husband. He said he would like to cry but can’t.

LIZA

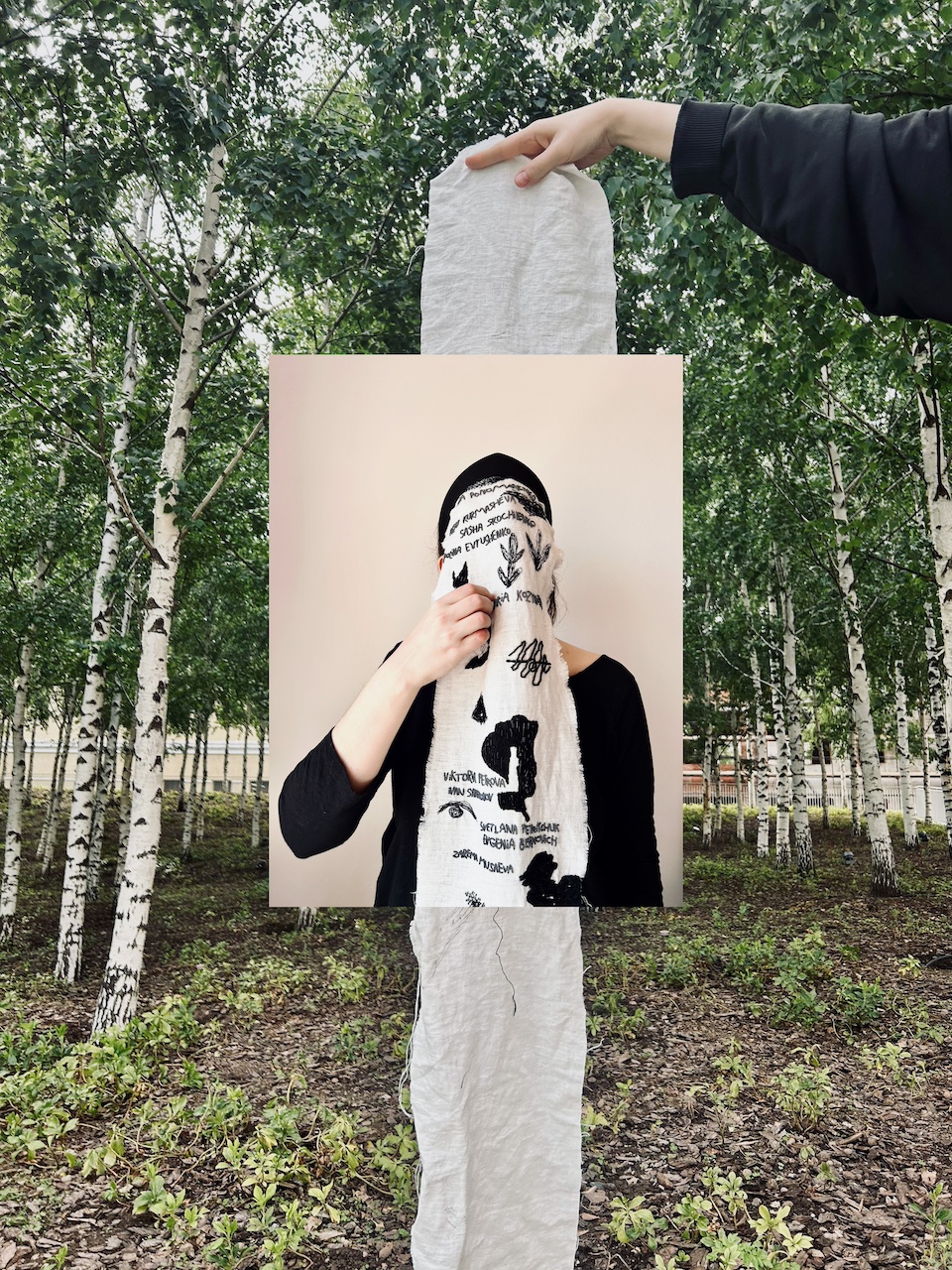

The second collective project was *Bir(c)hmarks* (a wordplay on »birch« and »birthmarks«) with the names of political prisoners. For this, I asked friends and acquaintances to draw birch marks, which I then embroidered with threads and beads. So far, about twenty names have been embroidered, and two of those people have been released, which is very heartwarming. I don’t plan to remove these names, as these individuals suffered for their beliefs.

LIZA

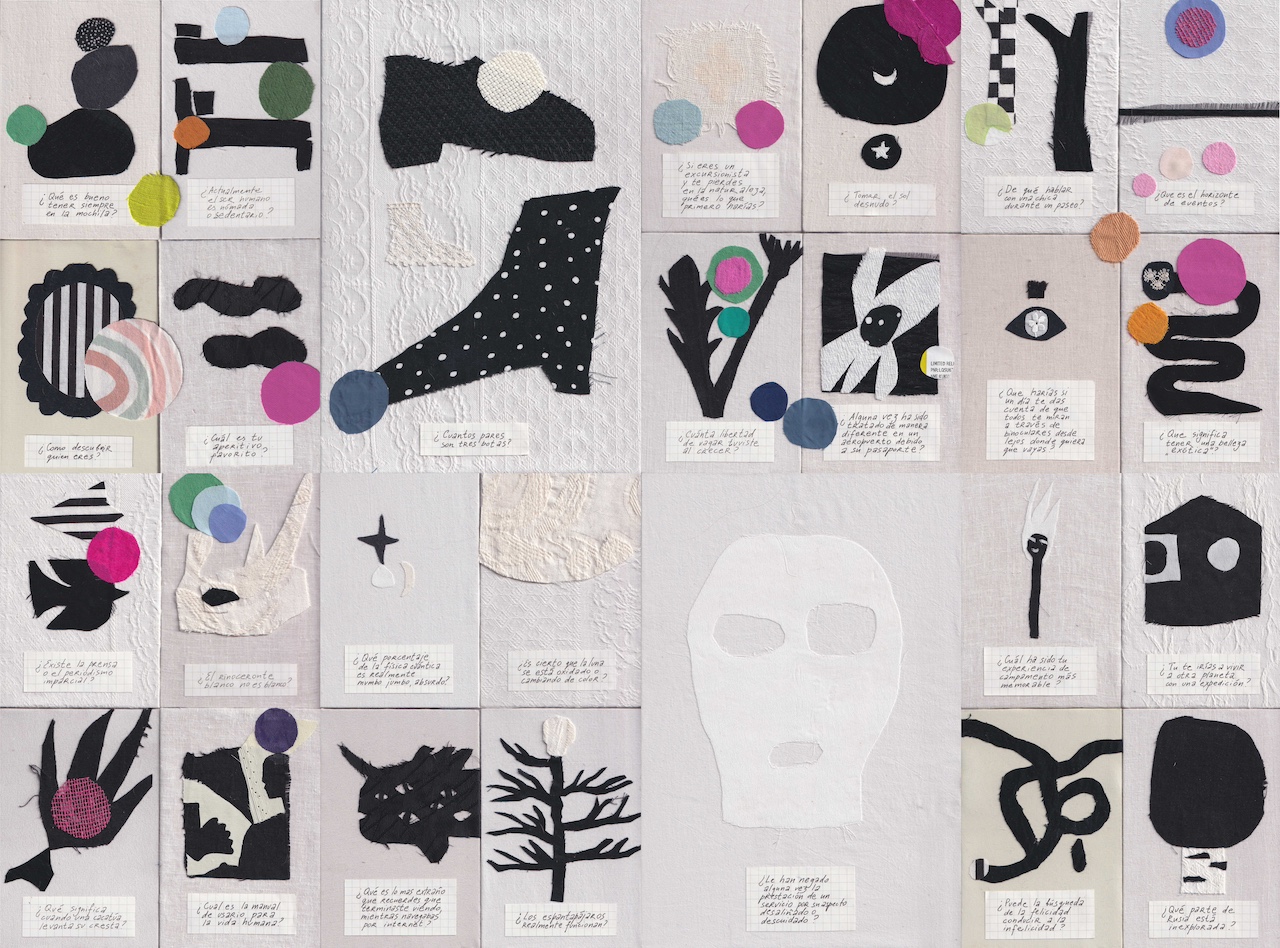

These are all long-term projects I’ve been working on since 2023, and I continue to develop them. Recently, I felt the need to take a break and create a very simple project, where people answered questions ranging from abstract to deeply personal ones that we ask ourselves to stay grounded in the world. Based on my associations with these questions, I made textile collages and asked my friends to respond—this was my way of capturing the importance of social connections in exile.

I usually collect responses via Instagram and Telegram, but for this project, personal meetings were especially significant to me.

How has immigration influenced your artistic practice? Do you engage with local cultural institutions?

I lived my whole life in Saint Petersburg and had no experience of moving, so immigration was initially very difficult for me, and I experienced a lot of anxiety. I didn’t fully realize what was happening. Doing manual work became a way to get out of this state and live through the experience without postponing it. I had threads and needles with me, and I started embroidering in Georgia in the spring of 2022, almost immediately after moving.

Before that, I was reluctant to consider myself an artist; I thought it was a serious pursuit and that I didn’t have the potential for it. After moving, it became clear that now was the time to try something because there might not be an opportunity later. Although, in the moment, I didn’t think that way—it’s only now that I realize this in hindsight.

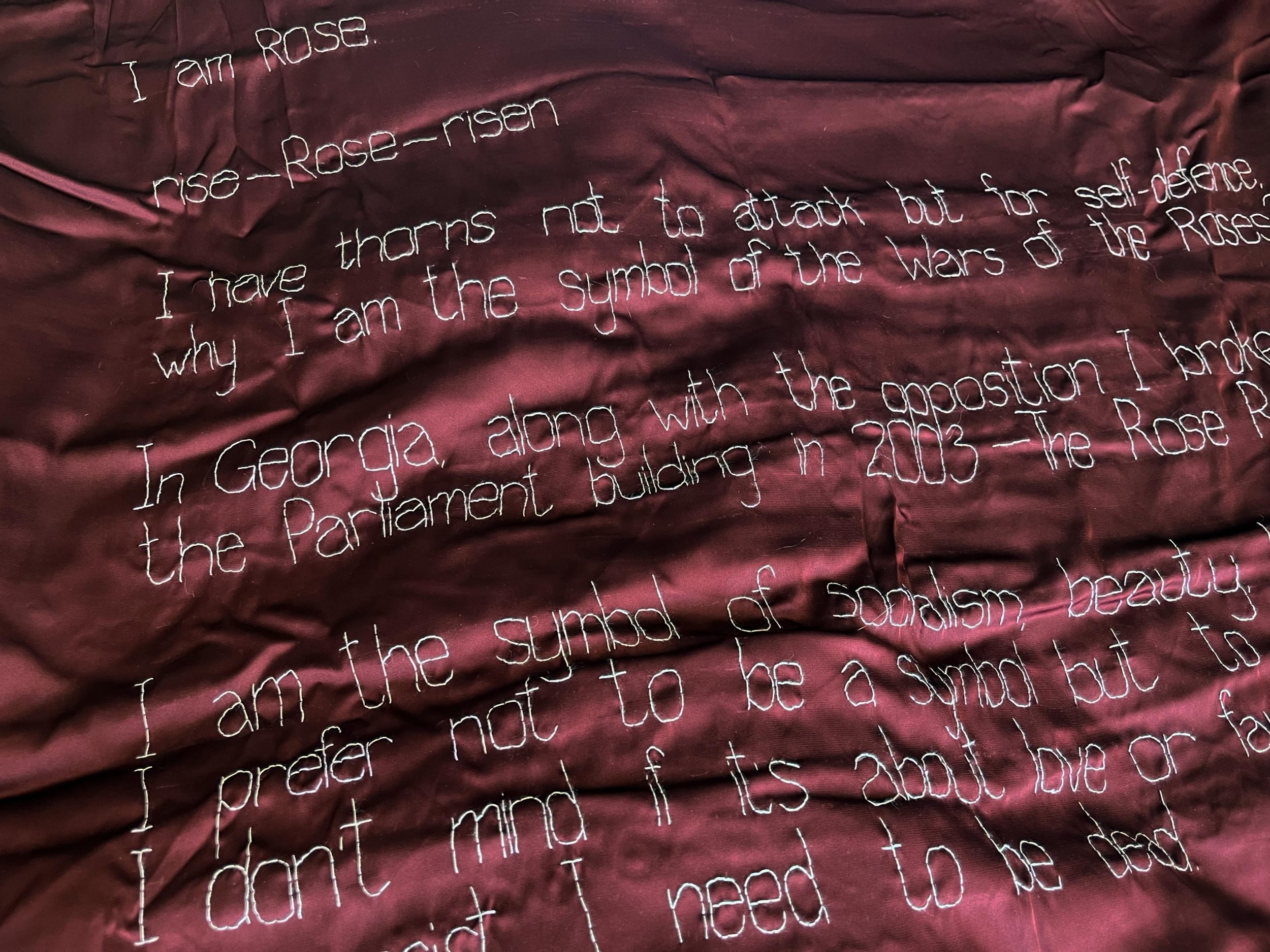

In Tbilisi, I participated in the anti-war festival »Myceliumi« organized by the group »Pobegi« which included artists from various countries. I created a work in English about the connection between flowers and political events. I chose three flowers and embroidered their stories on fabric.

LIZA

I also had the opportunity to participate in the Spanish festival »STRIPART« with a work about home and roots.

LIZA

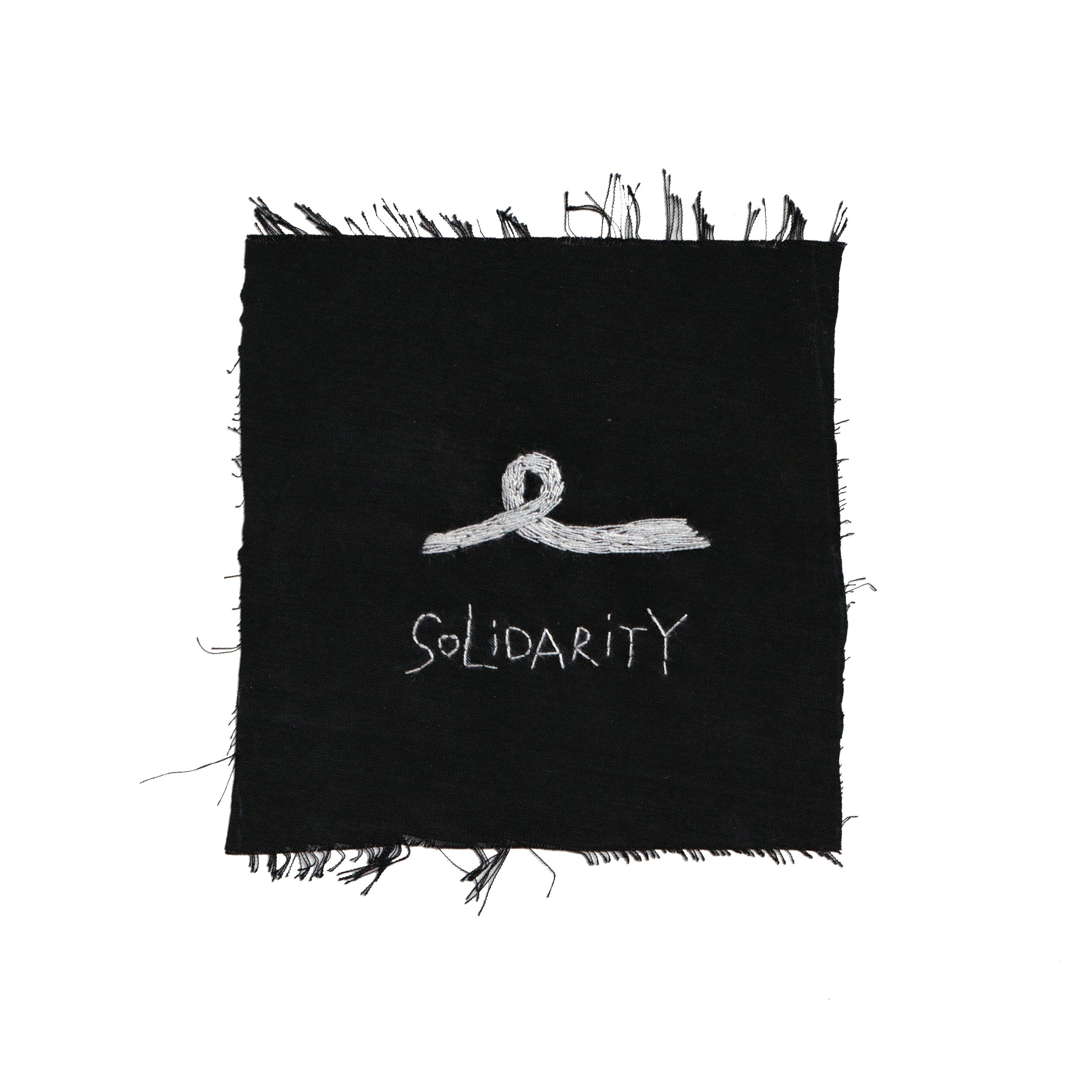

During Antiwar October organized by FAS, I embroidered 31 word related to war on black squares. The proceeds from the sale of the works were donated to non-profit organizations.

In your works, you use Russian, English, and Spanish. How do you choose which language your work will »speak« in?

For me, it’s always a difficult decision. It’s easiest for me to express my thoughts in Russian, and I enjoy when there is a play on words. In English, I create projects aimed at a broader audience, like in »Bir(c)chmarks«—I embroidered the names of political prisoners in Latin letters because I wanted them to be seen not only by Russian-speaking people.

I have fewer works in Spanish, and through embroidery, I’m more trying to learn the language, as it’s difficult for me. For example, I learned and embroidered a song by Violeta Parra, a singer from Chile. My Spanish teacher is passionate about art, and she teaches me through culture. We watch films, listen to music, and discuss feminism.

Who usually participates in your embroidery workshops, and what are their works about? In which language does it all take place?

My workshops are conducted in Russian, as I don’t feel confident in other languages yet. The participants are mostly immigrant women, and there are always common themes that emerge. I explain how text appears in textiles through words or illustrated stories. Each participant can embroider their own phrase. My general message is that the personal and the political are always intertwined, so the participants embroider something personal, but that resonates with what’s happening–with war, loss, and attempts to adapt.

Can artists be outside of politics today?

Art can exist outside of politics, but I don’t really connect with such artists. For me, the personality of the artist is important. I’m interested in those who are involved in what’s happening, those who emotionally resonate with it and reflect on it. In one way or another, all art is connected to reality, but it can be seen in different ways. It can be something direct, or it can speak through images about certain phenomena. For example, laws about relationships: love is personal, not political, but even it is regulated by the state. The play by Zhenya Berkovich and Sveta Petrichuk is not directly about politics, but it ultimately ends up at the center of political repression. I resonate with works that are nuanced, which don’t shout but leave space for my feelings and reflections.

Earlier, I thought that politics wasn’t my concern, that it was the business of other people. But probably after meeting my husband, I began to see things differently. He’s from Belarus. Shortly after we met, protests broke out in his country [in 2020]. Through his feelings and emotions, I shifted to my current worldview. I began to notice that all problems are interconnected, and they all affect us. Then came COVID, and later the full-scale war in Ukraine. I’m especially concerned about the issue of violence against women in my country. And this is a problem that exists all over the world. Many of my friends, relatives, and just people I like are still in Russia. It’s important for me to empathize, to remain in confrontation with what’s happening, because it affects what’s going on in the world, and it’s impossible to just turn it off. Russia is my homeland, and I don’t renounce what’s happening there.

Photo credits: Lisa MUR