Vasilisa Palianina

Vasilisa Palianina (b. 1986, Minsk, Belarus) graduated from the Art Department of the Belarusian State University in the Design Faculty in 2009. In 2021 moved to Europe, where she currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

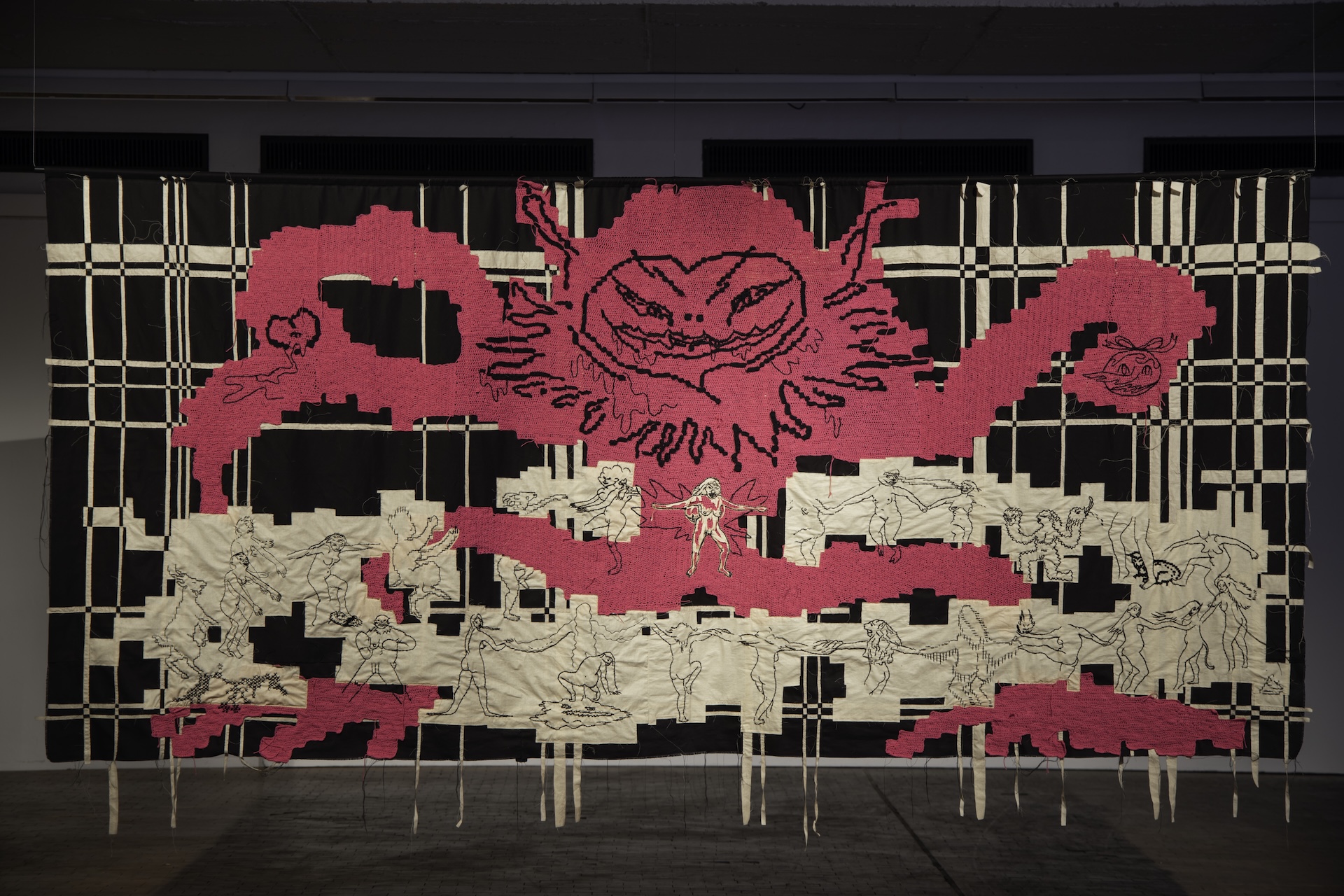

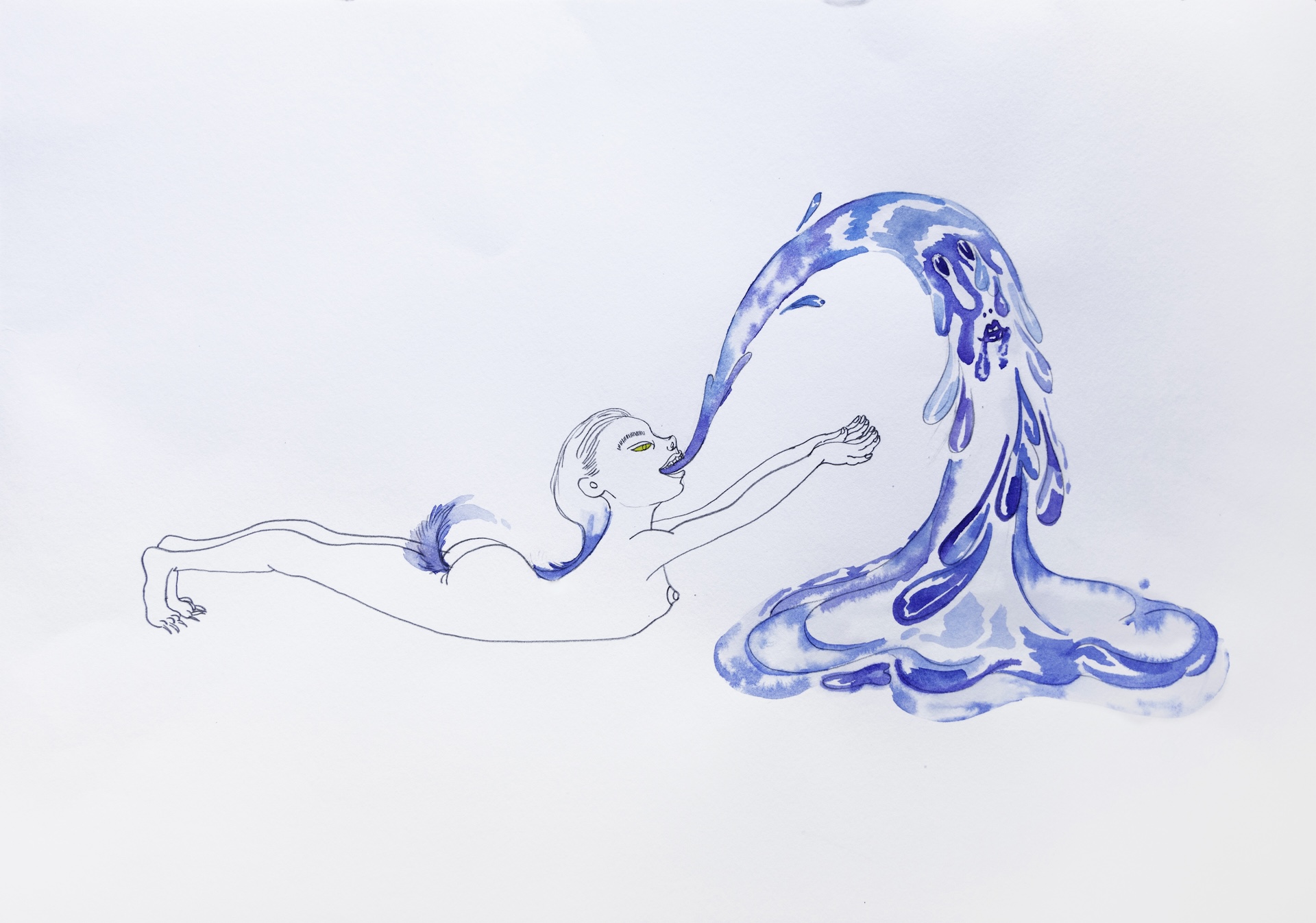

In her artworks ranging across graphics, installation, performance and experimental techniques, Palianina addresses the topics of sexual identity, gender, human and animal natures and Belarusian politics through mythology. The transdisciplinary artist participated in various residencies, including Gaude Polonia–Warsaw, Poland (2019), Slavs and Tatars art group, Pickle Bar, MRI, Akademie der Künste–Germany (2022–2023). In 2019, together with the painter Andrey Anro, she founded the art group »Who Except Us« and in 2023 joined the art collective »Shklatar« (with Andrey Anro and Aliaxandar Adamau).

Photo credits: Ira Jihila.

»Larisa«, your project dedicated to the memory of your grandmother, is perhaps the only one of your works that does not explore themes of nudity, sexuality, animalistic instincts, or a kind of pre-civilizational freedom of expression. Given that we were both born and raised in an environment where these subjects remained taboo for decades (after all, in the USSR, ‘there was no sex’), my first question is this: What initially drew you to these themes, and what continues to hold your interest in them? Is it curiosity, fear, or a deliberate challenge to the modesty of introverted Belarusians?”

At the moment, I find myself in a state of absolute liminality, and your question feels as though it describes another artist, not me. In a sense, my entire practice has been reset to zero, and I, too, am in a state of crisis.

However, I don’t perceive crisis as something inherently negative; rather, I see it as the next stage of my existence, albeit difficult and elevated. In this state, my responses today feel less like my own thoughts and more like an immersion into a film—one in which I am merely an observer rather than a participant.

As for sexuality and freedom in projects in general, I don’t see them as a challenge to conservative society. After all, we all have secret desires kept behind closed doors. The difference is that I am, by nature, an open person—my doors have no locks. I have always been irritated by the phrase: »Don’t air your dirty laundry in public.« I find it hypocritical because people only wish to present a polished version of themselves in public, whereas their true nature is revealed in the intimacy of private space. That is where my curiosity lies and where I feel most curious to explore.

By the way, I would not say that »Larisa« is devoid of nudity. This is a very personal project that exposes my family relationships, dreams, and anxieties.

Have you ever made an art piece that unsettled or scared you—either during the process of its creation or after it was finished? Do you sleep well, in general, after being immersed into art?

My works never scare me. They are not about horror or fear but rather about the mythology of reality, about different variations and possibilities of parallel worlds, where characters either never cross their paths, or, vice versa, merge to give birth to entirely new forms and narratives.

In general, I see the act of »bloodletting« as profoundly therapeutic—when unsettling or traumatic subjects do not remain locked inside you for years, corroding the soul, but get released, processed, and transformed through creativity. But, unlike psychotherapy, where I engage with my experiences analytically, fully conscious of their personal significance, in art, these questions take on a life of their own—partially or even entirely beyond rational control. And it is creativity’s ability to break free from established patterns and boundaries that I find most beautiful.

Who inspired you in your early artistic searches, and how did you react to the responses from those around you? I dare to assume your art could have been perceived by some as rather unsettling.

I am always inspired by something or someone: book and film characters, people, animals, and, most of all, my beloved dog, who passed away seven months ago. His absence remains deeply painful.

For me, inspiration is about the inner joy of creation. Experiencing it feels like returning to your inner child. And what does it mean to be a child? It means being able to get amazed, to experience an insatiable curiosity for the new, a hunger for discovery, the absence of rigid mental rigid frameworks. It means embracing pure, limitless imagination.

At the beginning of my artistic journey, I was influenced by Kiki Smith and Louise Bourgeois. Later, I discovered Marlene Dumas, and, on the whole, my knowledge of contemporary art enriched significantly thanks to Irina Kulik’s lecture series Asymmetrical Similarities. I still rewatch them from time to time and remain deeply grateful for them.

I also find sincere inspiration in children’s creativity. There is something profoundly pure and direct in the way children approach art—an instinctive, unfiltered freedom that makes their works feel fresh and uninhibited.

»Metamorfoze« is one of your central graphic projects started back in 2018. And how have you changed in the course of this time?

I would use the word »developed« rather than »changed«. I firmly believe that, by their very nature, people do not fundamentally change. They can evolve, uncover new facets or deepen their understanding of things—influenced by circumstances or choices—but their core essence remains intact. This essence is our character: some of its aspects are shaped over time, while others are inherent from the very beginning.

In 2018, I also experienced a major turning point—the end of my first marriage, a long-term family relationship. My life changed significantly, and navigating that stress allowed me to discover new sides of myself and broaden my approach to both creativity and life. That same year, my future husband, Andrey Anro, became a profound influence on me. As an artist-researcher working with archives and memory, his practice demands discipline and consistency—qualities I had lacked at the time, as my own work was more rooted in sensuality and fantasy. Gradually, I began to see creativity not just as a means of sublimation and self-expression but also as a form of analysis.

Performance »Peekaboo« (2018). An attempt to hide, to close yourself from problems. As a result: immersion in it to the fullest extent.

In this regard, I would also be interested in comparing the feelings you had in Belarus, Poland, where you lived for a while supported by »Gaude Polonia,« and, finally, Berlin. In which of these rather diverse cultural and social environments do you experience more resourceful states for doing art? Where can you breathe more freely and why? And can an unfriendly environment also, to some extent, »help« to create—that is, to give the necessary incentive (trigger?) to work against the odds? Or is it rather exhausting?

Let me start from the end. Yes, working against the odds is exhausting—just like arguments, conflicts, and the constant need to defend or justify your point of view. But the key question is: Why are you doing it? On the whole, it is important to understand this elsewhere, too. It might be tempting to place yourself into a bubble of comfort, but there is always a risk of getting stuck there.

For me, location, or country, is not what matters much, as I am continuing to work with Belarusian context, so to say. My inner freedom is not tied to geography. What matters most is a sense of security—that is my priority. My family is also a priority; I need to have my husband and daughter around, as their presence makes any place feel like home.

Warsaw and Berlin are, certainly, very different cities, in terms of freedom and opportunities. Naturally, it is more attractive to be in a place that offers more self-realization. But here, in Berlin, over the past year, we have faced numerous emigration-related problems and the attitude we experienced was neither supportive nor friendly. This has led me to rethink the concepts behind some projects of mine—especially »Forest Faces«, where I initially explored the theme of queer outcasts in a conventionally conservative society.

Now, I am myself to be such an outcast in an alien country which throws me up despite its outward claims of democracy.

The Kiss-Forest Faces

Photography, video, installations, art books, textile, graphics and ceramics–these are just some of the few media you freely use in your art. However, despite this amazing palette, your style demonstrates that you remain true to yourself keeping the symbolism of paganism, transgressive sexuality and disregard for any taboos. The question is–how do you choose this or that material, how do you choose it (or it chooses you) for a certain statement?

When it comes to choosing materials, the process is quite simple—it indeed depends on the project and the idea. Sometimes (quite often, actually), it’s also driven by an impulsive desire to experiment with something new. I am not the kind of artist who sticks to a single visual language for comfort and stability—though there’s nothing wrong with that approach, either. I enjoy exploring different materials because each reveals something new about both the work and myself. For example, working with ceramics made me realize that clay has a life of its own—you don’t simply manipulate it; you learn to negotiate with it. My works are never conventionally perfect—they crack, lose balance, or remain slightly unstable. But this imperfection fascinates me; it serves as a reminder of life’s fragility.

Thanks to »Shklatar«, I have also been experimenting with 3D printing, which requires a completely different approach—structured and systematic. In this, I have great support from Sasha [Alexander Adamau] and Andrey. Overall, I truly enjoy working as part of our team. We are all different artists, and it is precisely this diversity that allows us to create unique pieces that complement each other.

Among other things, the choice of material shapes my approach to the creative process. Embroidery, for example, involves calm, precise work that engages fine motor skills. When sketching, I find external distractions disruptive, but when embroidering, I can listen to music, audiobooks, lectures, or even watch films. These two processes require different levels of emotional involvement.

In 2019, as part of »Gaude Polonia«, you made »Night Club« art book, where forest drawings on the pages of a Belarusian passport, visible only in ultraviolet rays, were intertwined with pagan myths, and in an interview for CityDog you spoke about the peak point of contact between these realities–the search for a »paparac kvetka« (fern flower)–as a metaphor for conceiving a child. Recently, you and Andrey found your flower and became parents, so I can’t help but finish the talk with a question about this new page in your life. Is there a feeling (anticipation) of a new chapter not only in an existential sense, but also in terms of future creativity? Will the birth of a child also change you as an artist?

Yes, once you’ve found the »paparac kvetka«, life will never be the same—that’s its magic. I have mentioned earlier that I am going through a crisis, meaning that the stage of transformation is already underway. It’s hard to predict where it will lead me; I’m not sure my direction will change radically, but the path will undoubtedly expand and become enriched.

I am looking at my baby now, feeling immense happiness and unconditional love. But one day, the flower will grow teeth—and perhaps then she will be able to tell us what we taste like.