Wai-Hang Siu

A Hongkongese artist in forced exile explores creative ways to keep connected to his home through travelling postcards

Wai-Hang Siu is a hongkongese photographer, currently based in the UK. His work uses different methods and photographic principles to express Siu’s solicitude for society and his contemplation on the medium. History threads Siu’s practice and is the vessel through which he uncovers the worldview of being a Hong Konger. The subject matters are coupled with his take on the nature and strength of photography, highlighting the encounter between traditional photography and contemporary digital work.

Siu received the FORMAT Patron Award 2023, the First Price of Hong Kong Photobook Dummy Award 2021, the Hong Kong Human Rights Art Prize (2018) and the WYNG Masters Award (2014 and 2016). He was also named ifva Emerging Talent in 2016. His works are in SFMOMA, The New York Public Library(US), M+ Museum(HK) collections, and private collectors worldwide and exhibited in The United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Israel and mainland China.

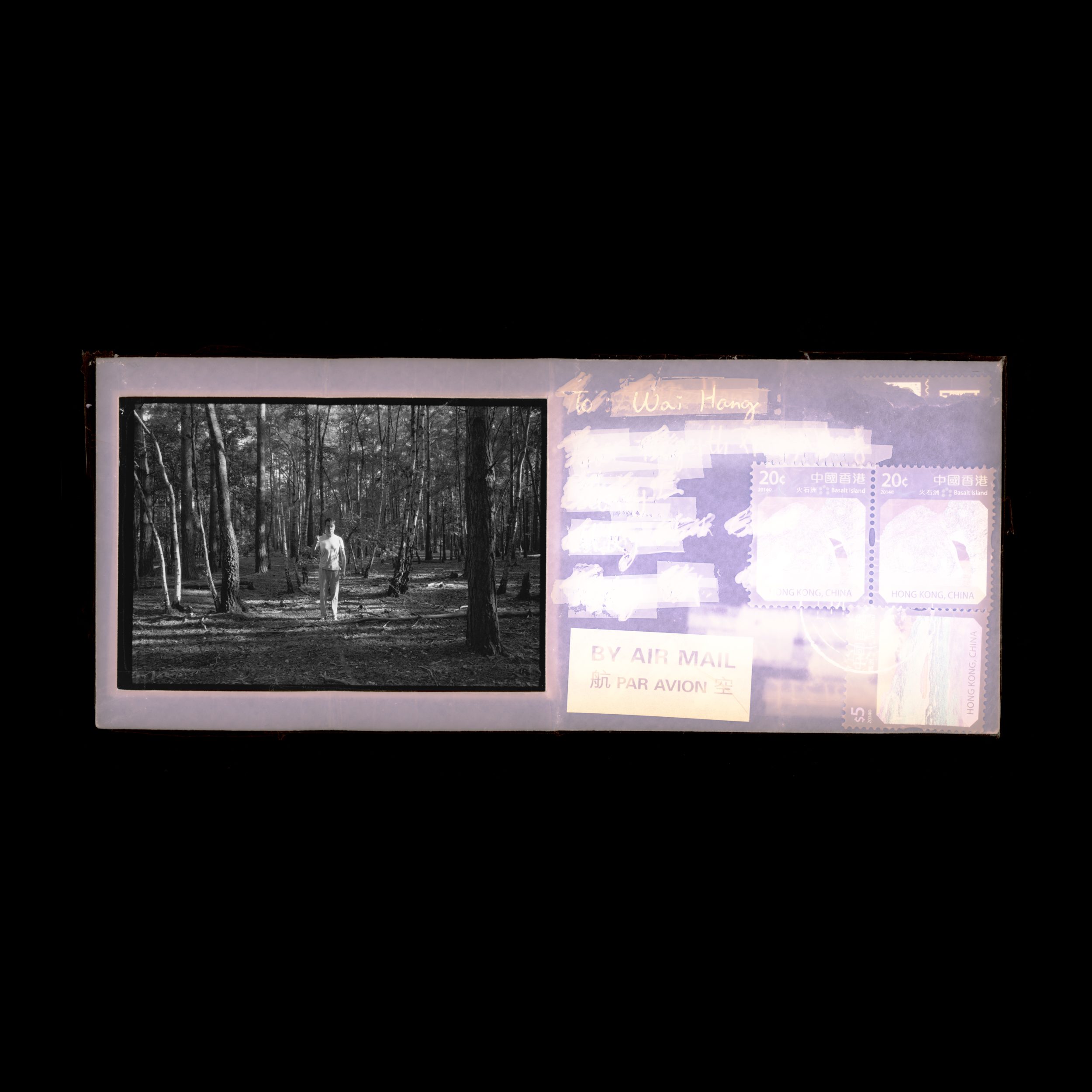

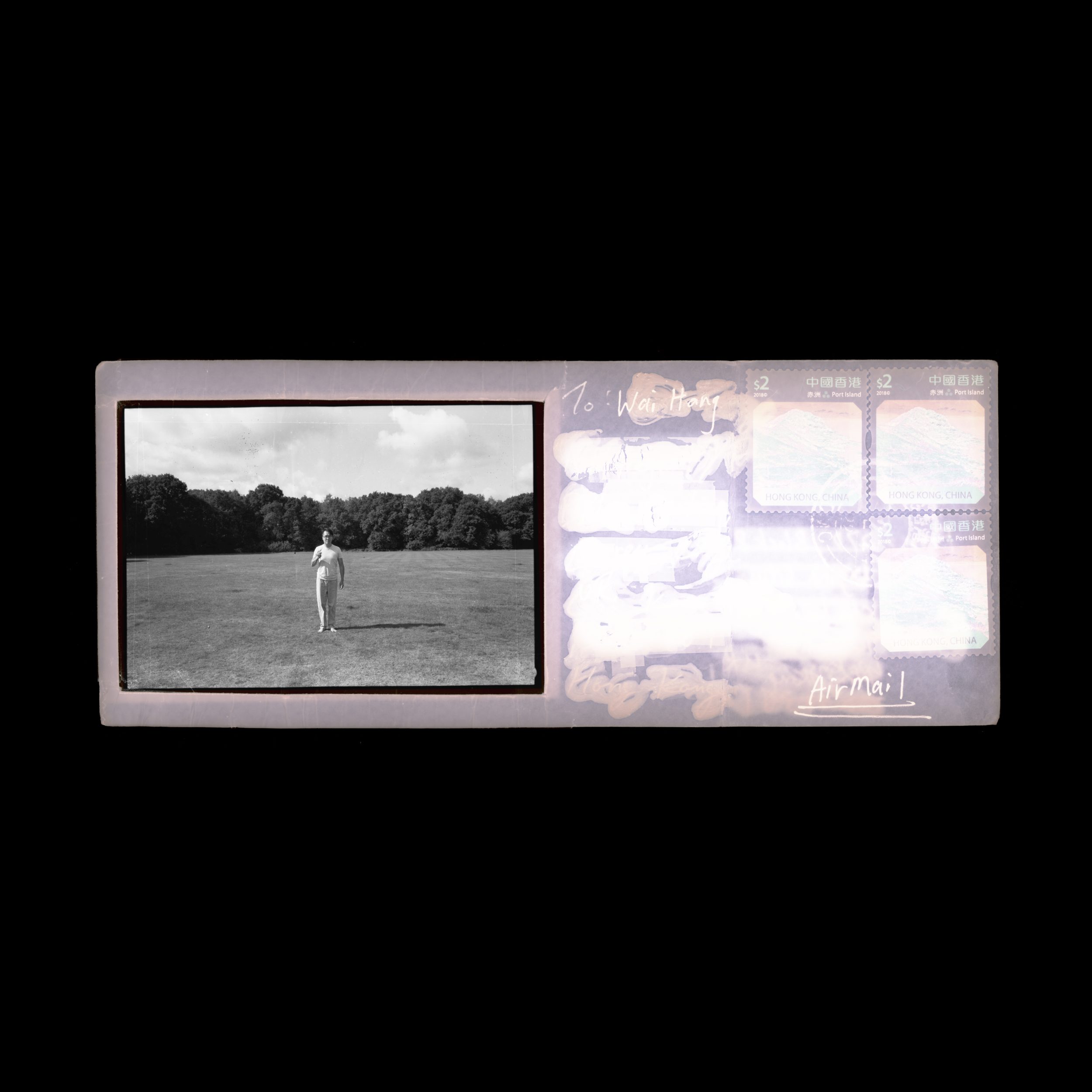

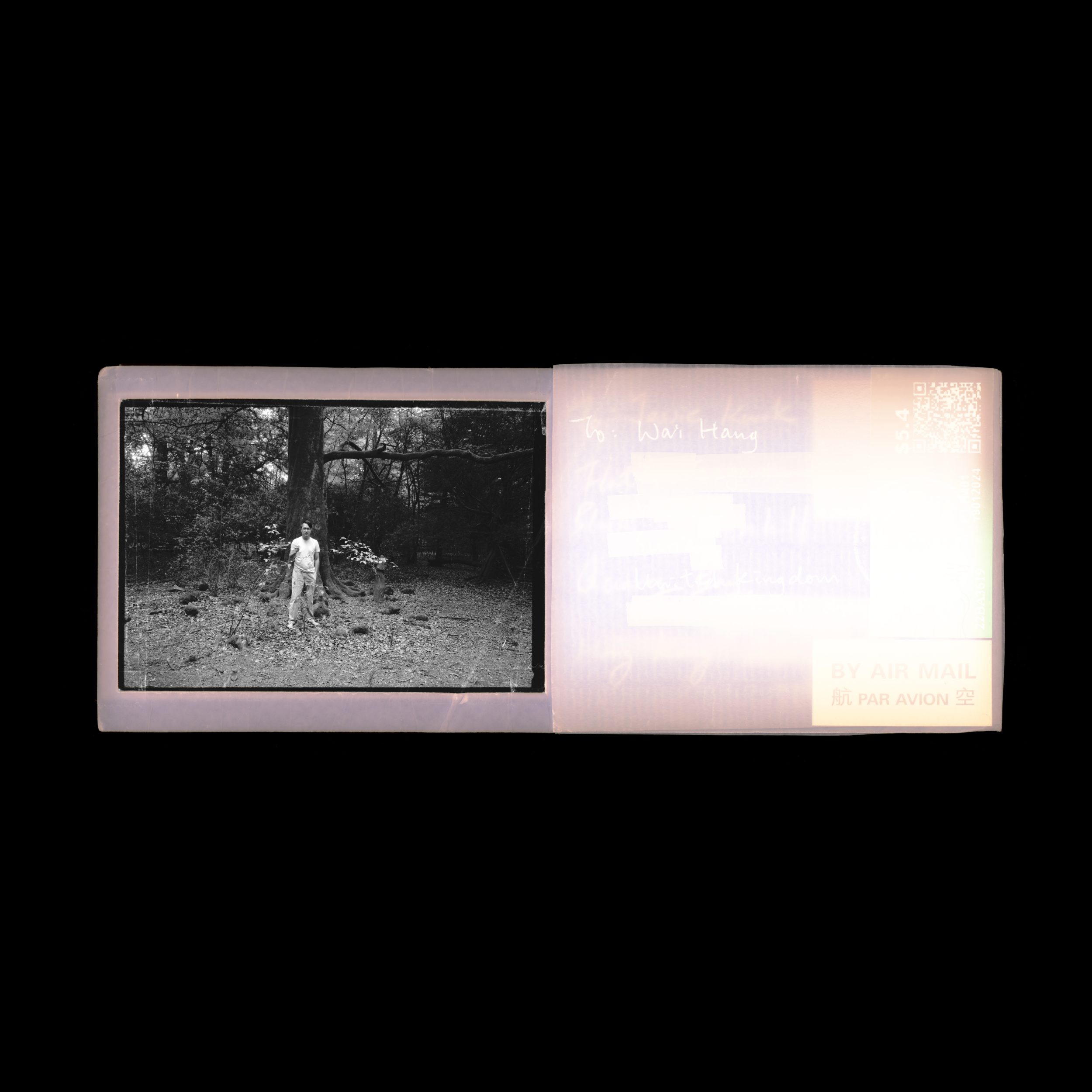

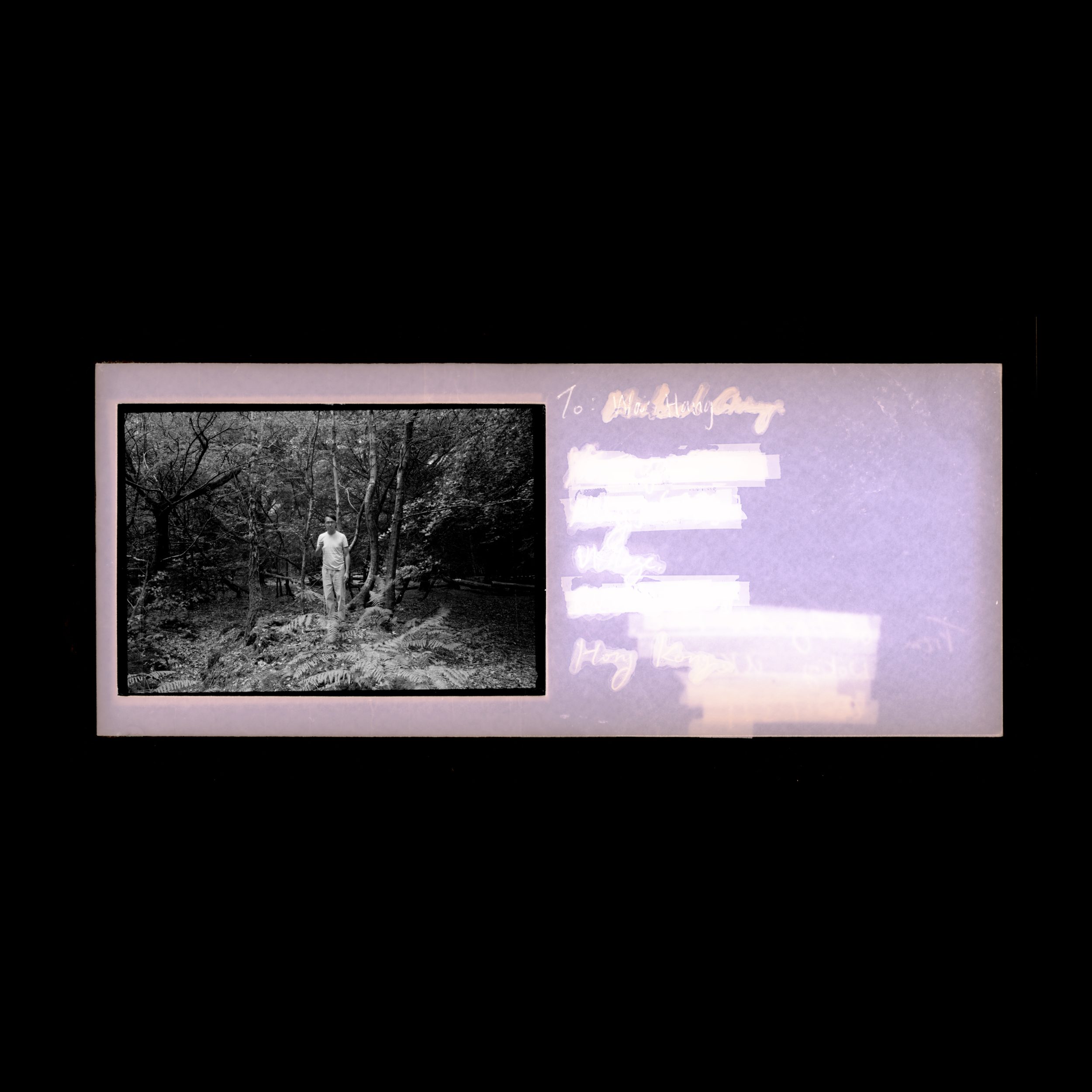

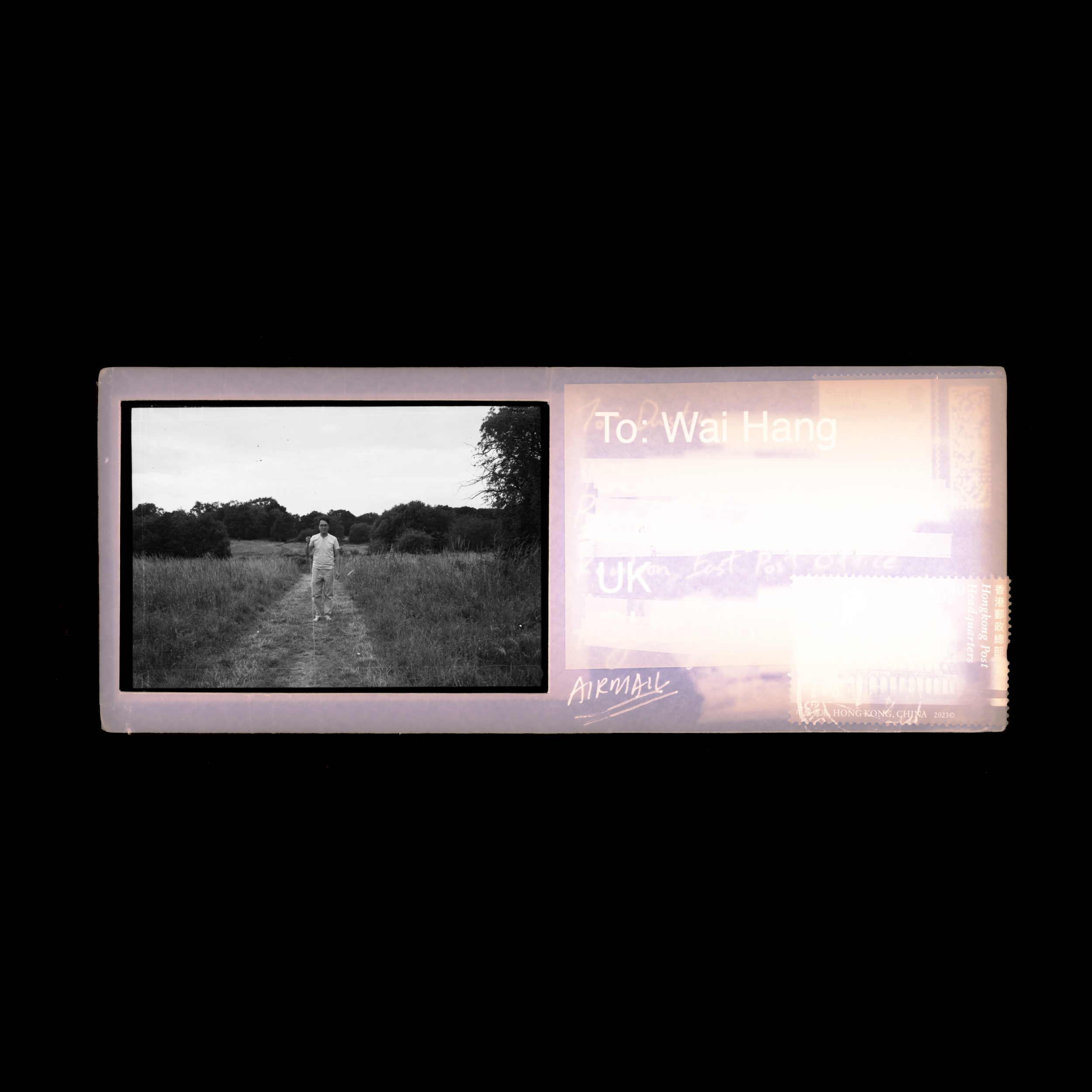

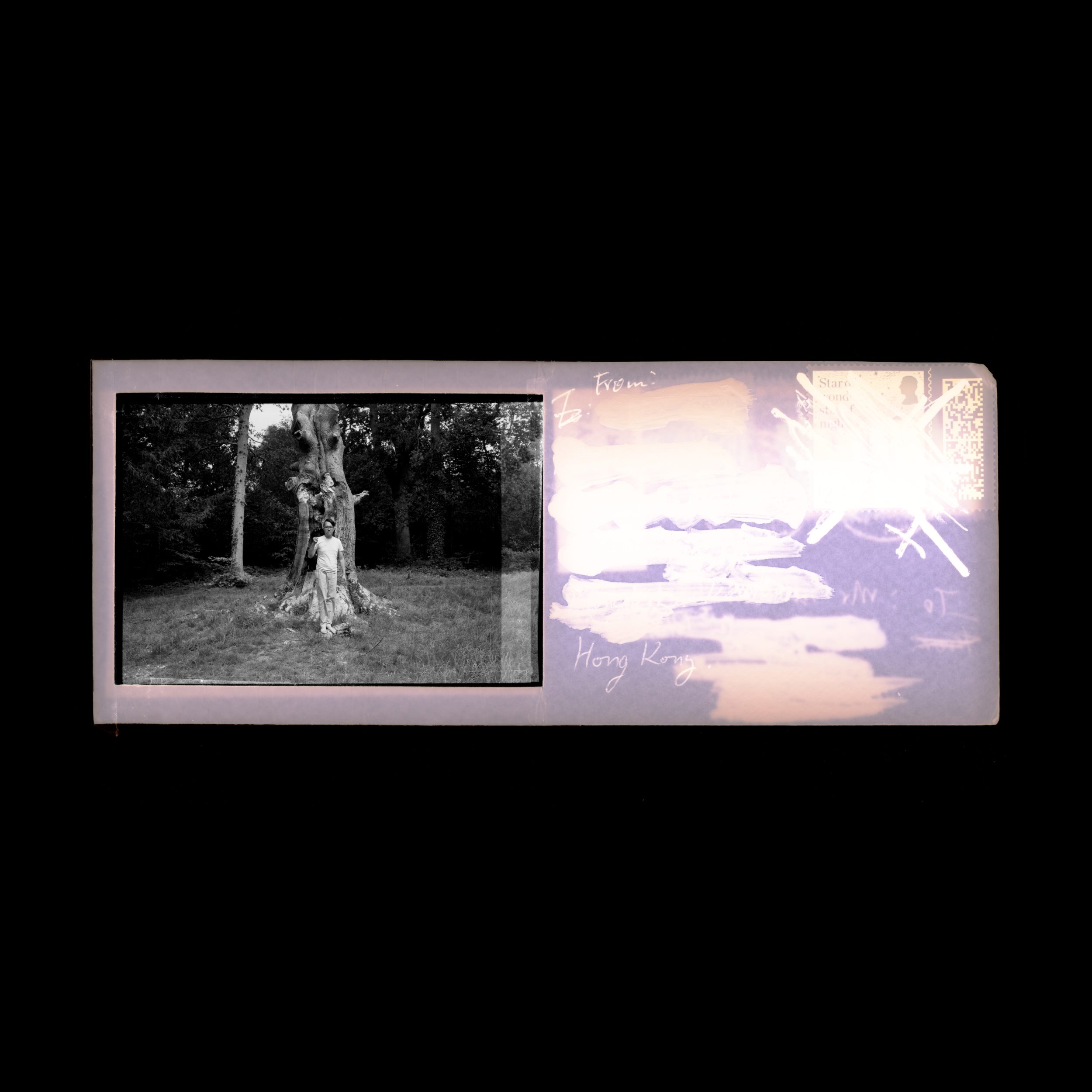

The project Postcard (Roundtrip) has been a form of meditation for me. Every person in exile feels homesickness at some point, longing for the connection to their homeland. Through this project, I found an alternative way to »return« to Hong Kong and »visit« my friends and family. By sending a postcard featuring my self-portrait on a symbolic journey back to Hong Kong and then having it returned to the UK, I was able to recreate a sense of connection despite the physical distance.

The marks and damages that appeared on the postcards during their journey became metaphors for the invisible wounds I carry as an immigrant. These imperfections reflect the emotional pain I’ve felt since 2019—a pain that has never truly subsided and likely never will. Yet, this project gave me a way to externalize those feelings and process them.

More than just a creative act, this project has become a means of preserving a fragile thread of connection to Hong Kong. While it doesn’t heal the harm, it offers a small but meaningful comfort, reminding me that even in separation, I can still maintain ties to the place and people I hold dear.

I left Hong Kong in September 2022, a decision I made in February of the same year. It was an incredibly difficult time for me and for society as a whole. The National Security Law had been in effect for nearly a year, effectively silencing dissent, halting protests, and eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy. Criticizing the government became dangerous, and as an artist who had always responded to societal issues, I found it impossible to express myself or live freely in such a restrictive environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic further revealed the extent of the government’s authoritarian control. People were coerced into vaccination, much like in mainland China, and those who couldn’t or didn’t want to comply were marginalized. Doctors who tried to issue medical exemptions were arrested, showing how politics overshadowed professionalism and basic human rights. At that point, it became clear to me that Hong Kong had fundamentally changed.

The global context also weighed heavily on my decision. The Russian invasion of Ukraine occurred the same year, yet there was an unsettling silence in Hong Kong about the events. This reinforced my realization that Hong Kong was distancing itself from international values and aligning more closely with China and Russia. I saw no hope of the city returning to the open, global outlook it once had. With my family’s future in mind, I knew we had to leave.

The UK became our destination because of the British government’s historic responsibility to Hong Kong. In response to the National Security Law, they introduced a new immigration route specifically for British National (Overseas) passport holders. As I was born in British Hong Kong, I qualified for this visa. It was the most practical option in terms of cost, time, and process. Moreover, the UK’s legal system, values, and way of life—apart from the weather—were familiar to us due to Hong Kong’s colonial history. This alignment made it easier for us to restart our lives in a new yet somewhat familiar environment.

The most challenging part of starting my first project in exile was that »Hong Kong« had always been my central subject. Leaving the place that inspired me so profoundly meant disconnecting from the source of much of my creative energy. For nearly a year, I found myself uninspired, as my family and I were entirely focused on resettling and rebuilding our lives.

However, this period of transition also gave me time to reflect on my identity and purpose in the context of my new reality. I began to explore what Hong Kong meant to me in exile, how it shaped who I am, and how I could continue to respond to it as an artist. Fortunately, the UK has a deep historical connection with Hong Kong, especially the era I was born and raised in. I met many British people who had worked in or travelled to Hong Kong during its colonial years. Their warm recollections of that time helped me reconnect with my roots and let the local people understand why so many Hong Kongers have chosen to relocate to the UK.

Of course, there is a cultural gap, but what surprised me most is how multicultural and accepting British society is. People here come from all over the world, bringing diverse cultural backgrounds, and the community embraces this diversity with respect and openness. Even when gaps exist between people, they are bridged by mutual understanding, something that stands in stark contrast to Hong Kong, where everything has become increasingly aligned with mainland China.

I believe identity is always evolving, shaped by and interacting with our living conditions. Leaving Hong Kong meant letting go of some roles I held in the past, but it also allowed me to embrace a new role as a British-Hong Konger. This hybrid identity has clarified where I belong and defined my mission as an overseas Hong Konger. It is now part of my responsibility to preserve our culture and traditions, ensuring that future generations maintain their connection to their roots. This continuity is essential for keeping »Hong Kong« alive, even in exile.

Most importantly, I’ve realized that telling the true story of what has happened in Hong Kong is a central task I must undertake. Fortunately, my identity as an artist remains steadfast, regardless of where I live or the circumstances I face. Art has become a vital way for me to fulfill this mission. Through my creations, I can transmit my experiences, emotions, and reflections about Hong Kong to a broader audience. In doing so, I’ve discovered a deeper sense of purpose and resilience in exile.