Masha Pryven

Ukrainian photographer Masha Pryven speaks up on the problematic issues around the EU’s current perception of the full-scale invasion and the role of artists and art

Masha Pryven, an artist, working primarily with photography. In her work, she explores the relationship between the political and the private, interested in the forms of co-authorship and collaboration.

Masha was raised in Luhansk (Ukraine) and studied in Kyiv. A Fulbright Graduate Scholarship recipient, she holds a M.A. degree in Comparative Literature from Washington University in St. Louis, USA (2009–2011). In 2014, she moved to Berlin, Germany, and she has lived and worked there since. Currently she is an MA student at Berlin University of the Arts.

As an artist, Masha Pryven has exhibited both in institutional settings and non-art contexts, including NART, Narva Art Residency (2024), Rathaus Lichtenberg (2024), Immanuel-Kant-School (2023), Berliner BücherTisch (2022), GlogauAir Gallery (2022, 2021) and others. Among the recent group exhibitions, there are Roots Gallery in Pisa (2023) and the duo exhibition »double take/побачити« Kateryna Lysovenko, Masha Pryven at Kunstverein Grafschaft Bentheim (2023). Her first photography book The Way to Combray was published by Edition Frölich in Berlin in 2022.

One of Pryven’s collaborative projects See What I See was published in Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, edited by Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, and others, Thames and Hudson, UK, 2023. For the »ABC of WAR« project she received a Cultural Education Project Fund and follow-up support for an upcoming book based on it.

Photo Credits: Philippe Kayser

Two years have passed since the start of the full-scale invasion and ten–since the annexation of the Crimea and Russia’s attack on the Donbass region of Ukraine. During this time, the presence of the Ukrainian agenda in the media has decreased significantly, with the air time given to the coverage of other violent clashes and loud political events, although the war is still ongoing with hundreds thousands dead, missing or in captivity.

»I will answer you later, the Internet connection is really poor, we are in the basement–the city is bombed again,« answers Masha in Telegram, while I finish editing this text for PlatformB. And after seeing them, I realize that the war in Ukraine knows no time, Russian bombs cannot complain about »being exhausted« as some people sadly do, once they hear this »uncomfortable topic« mentioned again.

Masha Pryven is a Ukrainian artist working with the media of photography and investing the maximum of her effort to make Europe and the world aware of the life and courageous fight of her fellow citizens with the Russian aggressors. Currently based in Berlin, she regularly travels to Ukraine to keep in touch with her close ones and continue documenting the everydayness under shelling–just a thousand kilometers from us who read her lines and look at the photos of people whose life will never be the same again.

Photocover: »R–Recht« (eng: right). A collage from »ABC of War« collaborative photo project, in which the project participants, displaced Ukrainian youth, communicate their experiences fleeing and starting anew, and also respond to the political debate about the war in German society. (2023–ongoing).

You were born in Luhansk, Donbas region of Ukraine, then studied in Kyiv and St.Loius, the US, but eventually moved to Berlin. What do these cities mean to you and what each of them gave you as an artist in terms of your (visual) language, topics you focus on and approaches you appy?

Masha Pryven: I am from Luhansk—a city on the russian border that has been occupied since 2014. Now, it’s a place of no return. I spent my childhood and early adolescence there in the 1990s—difficult times, a turbulent decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, organized crime, electricity outages, anxiety, precarity, but also happy times—literature, poetry, longing for a bigger world, and the ability to share it all with friends. Literature helped me to emerge from those grim realities.

In 2005, I went to Kyiv to study. It was the city of my youth—vibrant, buzzing, magnetic, filled with dealings and hustling, with a sense of openings and possibilities, but also dangers, especially for young women. Self-expression, self-imagining, sexuality, the literary magazine »Sho«, writing, traversing and transgressing in the times of new beginnings —the 2000s—for both myself and the country.

Then, I received a Fulbright scholarship to study literature and critical theory in St. Louis.

It was the Obama era, also a time of promise for the USA. After two years there, I was able to recognize my privilege—receiving a stipend, having insurance, and studying in an ideal setting—and link them to the inequality and racial divides I witnessed in St. Louis. There, I volunteered for a center helping Spanish-speaking children who fled the US-Mexican border with their homework, many struggling to make eye contact. This was my first experience working with a traumatized community.

At some point, I returned to Kyiv. And then the war started in 2014. I left for Berlin, my family fled Luhansk, my grandmother lost her mind, and the world of promise collapsed, really.

Photo: A fragment of »See What I See« project

Where were you when the full-scale invasion of Russia into Ukraine started and how did this affect you as an artist? How do you see the mission of the Ukrainian artists in exile now, two years after the start of the war?

On February 24, 2022, I was here in Berlin, where I live, in the darkroom the whole day, developing films, not knowing. When my husband told me later that day that »they were trying to capture Kyiv,« I didn’t believe it, because it was inconceivable. I stayed, so to say, in that darkroom.

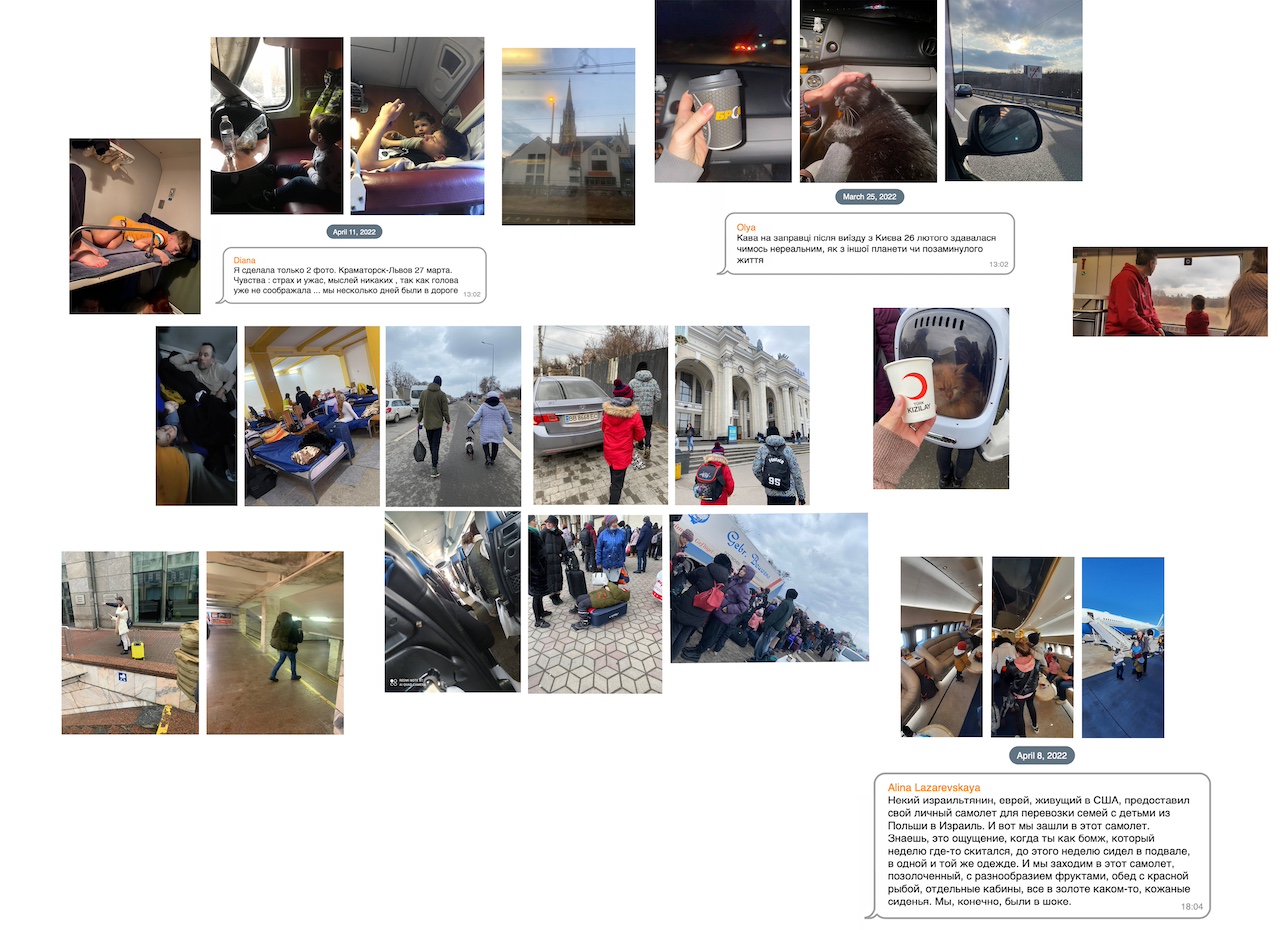

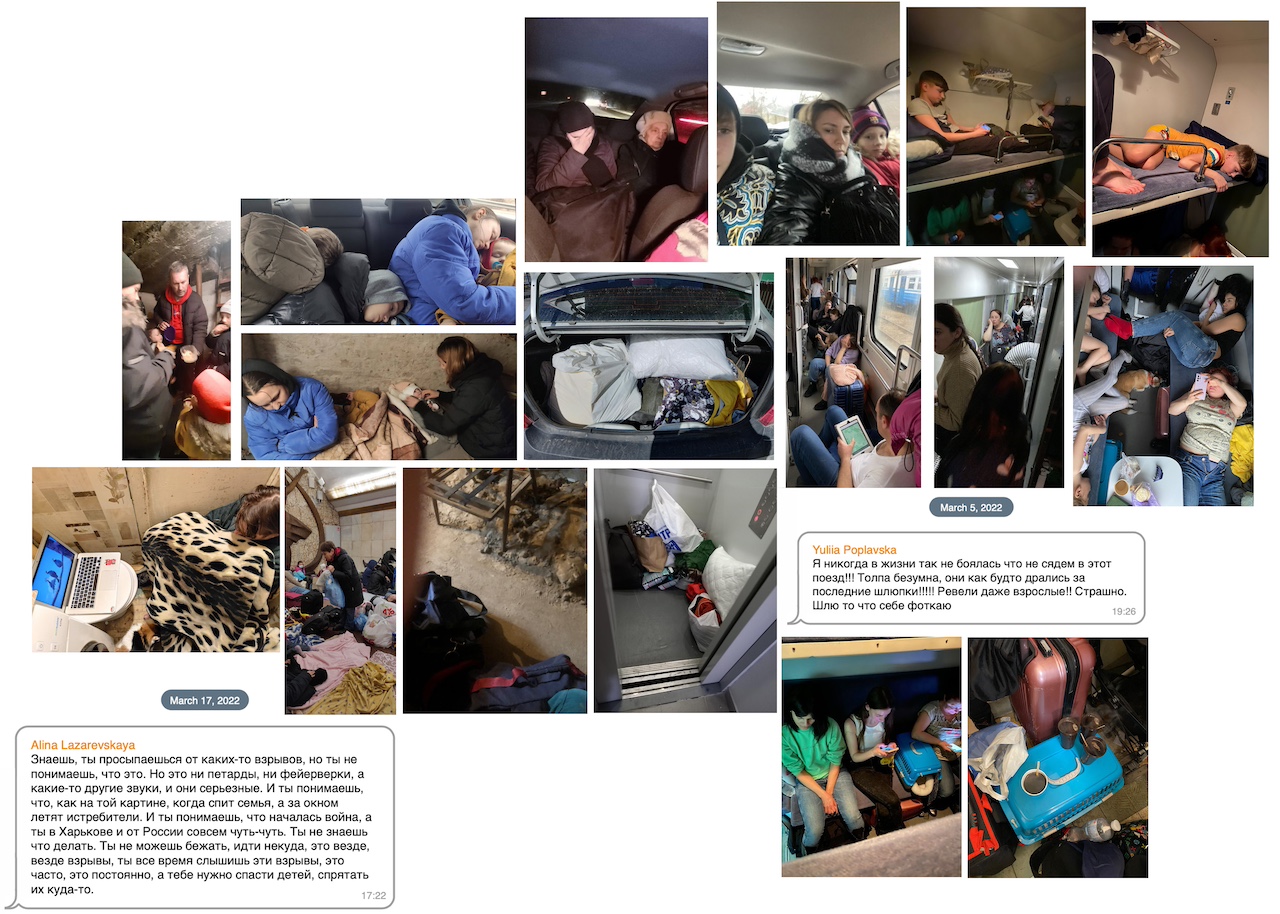

I needed a couple of days to fully accept the fact of a full-scale invasion and react and act as a volunteer. At that time, doing art was helping, and helping was doing art. I think my project See what I see (2022–2023) was born out of that sentiment. Ukrainians fleeing from the occupiers started sending photos and messages from their mobile phones to communicate their situation to us volunteers. I started collecting their photos right away. I was in contact almost daily with around thirty other Ukrainians for 1.5 years. They were documenting their lives with their mobile phones in different circumstances: fleeing, returning, living under occupation, and resisting. I formed a chronological archive of the photos, which became, for me, its own form of war photography.

Photo: A fragment of »See What I See« project

MASHA: This was my first collaborative work, and I felt that showing other people’s photos was, for me, the only right way to communicate what was happening to the German public at that time.

As for the mission you are asking me… I don’t think there is (or there could be) any. Displaced Ukrainian artists, mostly women, should take care of themselves and their mental health, and reflect artistically on whatever they feel like.

An important task is to engage the public into a conversation about the russian [spelling of Masha Pryven’s choice] war but also about patriarchy, institutional discrimination, and deeply internalized colonial arrogance here in the EU. But this is true for any artist who positions their work in a social and political context.

Do you feel that the attitude of the European audience has changed during this period? If yes, then in which way and towards what?

There is still attention on Ukraine, but it is dwindling. It is a difficult time for Ukrainians abroad, too. There is a lot of heaviness. You are always carrying the war inside you; it splits your mind and heart. Often, you are suddenly in disbelief: this ongoing devastation is geographically so close to Germans and yet so far for them. Several times in »Western Europe«, I found myself in conversations where someone »explained« to me that the international media portrays russia in a worse light than it deserves. I go to Ukraine regularly for my current project, and there I feel safer—psychologically—because when russian missiles fall on your head, it is just a fact, not an opinion of people who know about war from a screen. So, I think, generally, the gap between those who know, empirically or otherwise, and those who have an opinion is growing here. The last political race in Germany revolved around the war in Ukraine and, as a result, empowered those who have an opinion about what »peace for Ukraine« should be.

Video from »Passport« series. The Passport project (2024), a long-term collaboration with young people in Narva, Estonia, reflects on personal identity and challenges the institutional violence ingrained in an ID document. Narva, located on the Estonian-russian border, is where people possess Estonian, russian, and so called alien’s passports. The local population has largely embraced a one-dimensional »cultural identity« propagated by its imperial neighbor.

In March 2022, already in forced exile in Georgia, I wrote a rather emotional essay with the self-speaking title »Have You Suffered Enough?« where I shared my personal experience of accumulating negative responses from the wide range of EU institutions whom I had fruitlessly addressed for help. Back then I developed a feeling that there was a whole »victimhood competition« ongoing in parallel to endless conflicts that were springing up in different parts of the world and that in responding to people’s requests NGO bureaucrats somehow lost their sense of empathy and solidarity.

To which extent does this resonate with you and your reflections on the resources access and redistribution? Is it a state of affairs that we kind of need (have to) accept? Shall we (and can we?), as people rather outspoken in art, human rights defense, and activism »regroup« and coin our own strategies in the fight for respect and equality?

This is the politics of attention you are talking about. This is cruel; this works. After each terror attack committed by russia against Ukraine, significant enough in magnitude, support from the EU strengthens in terms of financial help and resources. This year, there was a missile attack at the Okhmadyt Children’s Hospital in Kyiv with oncological patients inside. The world has seen the aftermath—photos of children, some of them on IVs, with bald heads, sitting outside near ruins, waiting for evacuation. The question is: WHAT, which will be even WORSE, SHOULD happen to change the course of this war? And then—what country is the next one to be attacked by russia so that the Europeans will think it is THEM now? Germany? France? Maybe. Estonia? Latvia? Maybe not. How much will it take until THEM becomes US? Ukraine was very close, but obviously not close enough.

Photo: »S–Schule« [eng. school]. A collage from »ABC of War« collaborative photo project, in which the project participants, displaced Ukrainian youth, communicate their experiences fleeing and starting anew, and also respond to the political debate about the war in German society. (2023–ongoing)

MASHA: Returning to your experience with the NGO bureaucrats: as long as justice depends on selective empathy and not on political will and resolve to push back against bloodthirsty dictators and ensure global security, there will be a market of suffering. You know, today it is Ukraine; tomorrow it could be someone else.

And that is what many Ukrainian artists and scholars have been doing—and continue to do—they keep challenging the russian colonial lens through which Ukraine has been viewed in the EU for decades.

Do you reflect on that in your art?

I have done various works about the war in Ukraine, in which I reflect on war, language, and the representability of war. My next exhibition project is created together with Victoria Lykholot, an artist from Kharkiv, based in Berlin. We will invite different perspectives from various countries—all affected by russian imperial violence to varying degrees. We aim to explore the root causes of war and focus on women’s experiences, which are still largely overlooked in art, whether in times of war or not. We will also collaborate with each other in this exhibition and explore forms of transnational solidarity.

Germany is a EU state that has accepted around 1 million Ukrainian refugees. But I assume that many Ukrainians had been based here before, right? How connected is the Ukrainian diaspora (including the artistic one)? Are there any supportive key art figures that gather the newcomers around and help them to build their lives and careers anew in Berlin?

For me, it is difficult to say how connected the Ukrainian diaspora is. As for supportive figures in the art world, Boris and Vita Mikhailov, who live in Berlin, come to mind. I met them when I was starting out in photography in 2018, and they accepted me as a newcomer and have been supporting me ever since. Boris is an enormously important figure, not only in art and photography, but also as a teacher. In the course of our private conversations, I started to engage more deeply with the media I work with: photography and language, but also with the topic. My current long-term work about life during war, for which I regularly go to Ukraine, involves collective experimental writing and is a result of this engagement. I also learnt to see my work and works of my contemporaries as carrying larger ideological and political messages: what do you say about your subject, to whom and what does it mean for the topic?

I think throughout his oeuvre, Mikhailov has unapologetically reflected on the ideological violence of the Soviet regime on the body. In a way, many Ukrainian artists today are building upon that in the current context.

Photo: »P–Pazifismus« [eng. pacifism]. A collage from »ABC of War« collaborative photo project, in which the project participants, displaced Ukrainian youth, communicate their experiences fleeing and starting anew, and also respond to the political debate about the war in German society. (2023–ongoing)

Photo: »Q–Quelle« [eng. source]. A collage from »ABC of War« collaborative photo project, in which the project participants, displaced Ukrainian youth, communicate their experiences fleeing and starting anew, and also respond to the political debate about the war in German society. (2023–ongoing)

And to wrap our talk up, maybe I could ask you to share a few names and collaborative projects that have been recently produced by (or with the participation) of Ukrainian artists–also including those in music.

Here, I want to mention Yuriy Gurzhy, originally from Kharkiv, a musician, DJ, producer, and author. He moved to Berlin when he was 20. He is very active in both Germany and Ukraine, working within both contexts: his recent projects include composing music for an exhibition about Wassyl Stus at the Pilecki Institute in Berlin and collaborating with Serhiy Zhadan on their album Semafory, the third album of their duo Zhadan/Gurzhy.

I also want to mention Ganna Gryniva. Ganna, an exceptional jazz singer and musician, emigrated from Ukraine to Germany in 2002. She blends Ukrainian folklore with jazz, improvisation, and experimental music; she makes research trips across Ukraine to gather material for her work. Also, there is a very young Ukrainian band, Foso, from Enerhodar and Kupiyansk, based in Berlin, that creates a vibrant mix of downtempo, trip hop, and lo-fi genres.